Overview

Soft tissue sarcoma is cancer that develops in the tissues that support and connect the body. It can occur in fat, muscle, nerves, tendons, joints, blood vessels, or lymph vessels. It begins when a cell grows out of control, and instead of differentiating (developing) into a normal cell, it forms a tumor (lump). When sarcoma is small, it goes unnoticed or is ignored, since it does not usually cause problems. As it grows, it can interfere with the body's normal activities. It can also spread to other places in the body.

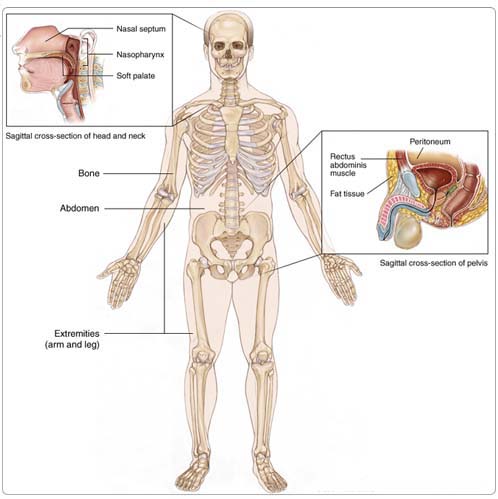

Sarcoma can appear in any part of the body. About 50% occurs in the arms or legs, 40% occurs in the trunk or abdomen, and 10% occurs in the head or neck. Sarcoma is rare, accounting for about 1% of all cancers. Most patients with smaller soft tissue sarcoma can be treated successfully.

Sarcoma is named according to the normal cells it most closely resembles (Table 1). Grade is the term a pathologist (a doctor who specializes in interpreting laboratory tests and diagnosing disease) uses to describe how aggressive the sarcoma is likely to be. Low-grade tumors usually stay in one place. High-grade tumors are more likely to spread to other places, a process known as metastasis.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing a disease, including cancer. There are risk factors that can be controlled, such as smoking, and risk factors that cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence disease, for many risk factors it is not known whether they actually cause the disease directly. Some people with several risk factors never develop the disease, while others with no known risk factors do. Knowing your risk factors and communicating with your doctor can help guide you in making wise lifestyle and health-care choices.

Most sarcomas do not have known causes. The following factors can raise a person's risk of developing sarcoma:

Previous radiation therapy. People who have been treated with radiation therapy for other cancers have a slightly increased risk of later developing sarcoma.

Genetics. People with certain inherited diseases, such as von Recklinghausen's disease (neurofibromatosis), Gardner's syndrome, Werner's syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, basal cell nevus syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, or retinoblastoma are at greater risk for sarcoma.

Chemicals. Workplace exposure to polyvinyl chloride (used in making plastics) or to dioxin may increase the risk of sarcoma. However, most sarcoma is not known to be associated with specific environmental hazards.

Symptoms

People with sarcoma may experience the following symptoms. Sometimes, people with sarcoma do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be similar to symptoms of other medical conditions. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your doctor.

Soft tissue sarcoma rarely causes symptoms in the early stages. The first sign of a sarcoma in the limbs or trunk may be a painless lump or swelling, which should be reported to a doctor. Most lumps are not sarcoma. The most common soft tissue lumps are lipomas, which are made of fat cells and are not cancer. People with sarcoma that starts in the abdomen may not have any symptoms or may have pain or a sense of fullness.

Since soft tissue sarcoma develops in flexible, elastic tissues, the tumor can easily push normal tissue out of its way as it grows. A sarcoma may grow quite large before it causes symptoms. Eventually, it may cause pain or soreness as the growing tumor begins to press against nerves and muscles.

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has metastasized (spread). Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis. Imaging tests may be used to find out whether the cancer has metastasized. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

There are no standard screening tests for sarcoma. A doctor should examine any unusual or new lumps or bumps that are growing to make sure they are not cancer. Sarcoma is very rare. This makes it important to consult a doctor who has experience with this type of cancer specifically.

A diagnosis of sarcoma is made by a combination of clinical examination and radiologic tests. It is confirmed by the results of a biopsy, a procedure in which a small amount of tissue is removed for examination under a microscope. The following tests may be used to diagnose sarcoma:

Imaging tests

Benign (noncancerous) and malignant (cancerous) tumors may look different on imaging tests. In general, benign tumors have round, smooth, well-defined borders. Malignant tumors have irregular, poorly defined margins due to their aggressive growth.

X-ray. An x-ray is a picture of the inside of the body. A chest x-ray can help doctors determine if the cancer has spread to the lungs. Typically, if an x-ray suggests cancer, the doctor will order other imaging tests.

Ultrasound. An ultrasound uses sound waves to create a picture of an organ and its contents. Tumors generate different echoes of the sound waves than normal tissue does, so when the waves are bounced back to a computer and changed into images, the doctor can locate masses inside the body.

Computerized tomography (CT or CAT) scan. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body with an x-ray machine. A computer then combines these images into a detailed, cross-sectional view that shows any abnormalities or tumors. CT scans can screen for distant metastases.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses magnetic fields, not x-rays, to produce detailed images of the body. MRI scans are useful to check for tumors in soft tissues nearby.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) scan. In a PET scan, radioactive sugar molecules are injected into the body. Cancer cells absorb sugar more quickly than normal cells, so they light up on the PET scan. PET scans are often used to complement information gathered from CT scan, MRI, and physical examination.

Integrated PET-CT scan. This scanning method collects images both from CT and PET scans at the same time, and then combines the images. This technique has the advantage of looking at both the structure and metabolism of the tumor and normal tissues. This information can be helpful in treatment planning and assessing treatment benefit.

Imaging tests may suggest the diagnosis of sarcoma, but a biopsy will always be performed to confirm the diagnosis and determine the subtype. It should be stressed that it is vitally important for a patient to be seen by a sarcoma specialist before any surgery or biopsy are performed.

Biopsy. A biopsy, either needle or incisional, will be performed. For a needle biopsy (usually a core needle biopsy, less often a thin needle biopsy), a doctor removes a small sample of tissue from the tumor with a needle-like instrument. In an incisional biopsy, the surgeon cuts into the tumor and removes a sample of tissue. In an excisional biopsy, the surgeon removes the entire tumor. A pathologist will then examine the tissue under a microscope to check for cancer cells.

Treatment

Through ongoing research, the medications used to treat cancer are constantly being evaluated in different combinations and to treat different cancers. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions.

The treatment of sarcoma depends on the size and location of the tumor, its grade, its subtype, whether the cancer has spread, and the person's overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan.

If the tumor cannot be removed by surgery, some tumors can be permanently controlled with radiation therapy. For tumors that can be surgically removed, radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may be given before or after surgery to reduce the likelihood of local and distant recurrence of the tumor. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy may also be used to reduce the size of the sarcoma and relieve pain and cancer symptoms. Chemotherapy may be given alone or in combination with surgery and/or radiation therapy.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for soft tissue sarcoma. The surgeon's goal is to remove the tumor and at least 2 cm to 3 cm (about 1 inch) of healthy tissue around it, to leave behind a clean margin. Small sarcomas can usually be cured by surgery alone, but those larger than 5 cm are usually treated with a combination of surgery and radiation therapy. Radiation therapy may be used before surgery (to shrink the tumor and make removal easier), or during and after surgery (to kill any remaining cancer cells).

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Most chemotherapy drugs are given by injection into a vein (called intravenous or IV injection). Among the chemotherapy treatments that might be used alone or in combination include doxorubicin (Adriamycin), ifosfamide (Ifex), gemcitabine (Gemzar) in combination with docetaxel (Taxotere) and paclitaxel (Taxol). The active drugs depend on the subtype of sarcoma: not all drugs are active on sarcomas. Chemotherapy for sarcoma can usually be given as an outpatient treatment. Most side effects of the drugs disappear within a short time after treatment. Chemotherapy is often useful in cases in which a cancer has already metastasized. A fast-growing sarcoma can be treated with chemotherapy before surgery. This often reduces the size of the main tumor and may destroy tiny areas of metastasis if some of the cancer cells have already drifted into other areas.

For large high-grade sarcoma, where surgery may not be possible or problematic, oncologists may recommend giving chemotherapy for three to four cycles before surgery to shrink the primary tumor, allowing surgery to be less radical. Some chemotherapy before surgery may also improve survival since it may kill cells that have broken away from the original tumor. Chemotherapy given before surgery is called preoperative chemotherapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or induction chemotherapy. Chemotherapy given after surgery is called adjuvant chemotherapy.

After the patient has recovered from surgery, the oncologist may give more chemotherapy to kill any remaining tumor cells.

Targeted treatments

New treatment strategies are designed to stop the growth of cancer cells at the level of genes and proteins. In 2002, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a drug called imatinib mesylate (also known as STI571 or Gleevec) for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in advanced stages. This drug is now the standard treatment for GIST. New target drugs are being tested. Sunitinib malate (Sutent) is a new drug that shows promise for the treatment of GIST, including for patients whose GIST is not treatable with imatinib.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to kill cancer cells. This may be done before surgery to shrink the tumor, so it is more easily removed. Or, it may be done after surgery to remove any cancer cells left behind. Radiation treatment may make it possible to do less surgery, often preserving the arm or leg. Radiation therapy also damages normal cells, but because it is focused around the tumor, side effects occur mainly in those areas. Most radiation therapy side effects disappear soon after treatment ends. Newer radiation techniques, including intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and proton beam irradiation, may improve the control of sarcoma, as well as reduce the frequency of shorter-term and longer-term side effects.

Advanced sarcoma

An advanced sarcoma is one that has recurred (come back) after treatment or spread to other sites at the time of diagnosis. The recurrence may be in the tissues where the sarcoma first appeared or in another place.

About one-third of patients treated for soft tissue sarcoma of the arms or legs have recurrence of their tumor-most likely in the chest. More than half of those treated for sarcoma of the abdomen or trunk will have some type of recurrence, which can be local, regional, and/or distant. Treatment of the recurrence will depend on the location and type of recurrence and on the method of previous treatment. An isolated local recurrence is usually treated with additional surgery plus radiation therapy. Treatment of sarcoma that has spread to other organs or lymph nodes may include surgery alone, surgery plus radiation therapy, or chemotherapy alone. Chemotherapy combinations are often used for advanced soft tissue sarcoma.

Patients who have been treated for sarcoma should have follow-up examinations at least every year to watch for recurrence. This should include a physical examination and chest CT scans or x-rays, and may include other imaging studies such as an ultrasound or MRI.

Patients who have been treated for soft tissue sarcoma should be particularly careful to report any new symptoms, such as a cough or a new lump. These may be signs of a cancer recurrence, or they may be side effects of treatment. Most patients who have been treated for soft tissue sarcoma should continue to have follow-up examinations for 10 years. If a recurrence happens, it is likely to be within the first two years, but some sarcomas recur much later. Most of these recurrences can be treated.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to sarcoma and its treatments.

Anemia. Anemia is common in people with cancer, especially those receiving chemotherapy. Anemia is an abnormally low level of red blood cells (RBCs). RBCs contain hemoglobin (an iron protein) that carries oxygen to all parts of the body. If the level of RBCs is too low, parts of the body do not get enough oxygen and cannot work properly. Most people with anemia feel tired or weak. The fatigue (tiredness) associated with anemia can seriously affect quality of life and make it more difficult for patients to cope with cancer and treatment side effects.

Appetite loss. Appetite changes are common with cancer and cancer treatment, including chemotherapy. Individuals with a poor appetite or appetite loss may eat less than usual, not feel hungry at all, or feel satiated (full) after eating only a small amount. Ongoing appetite loss can lead to weight loss, malnutrition, and loss of muscle mass and strength. The combination of weight loss and loss of muscle mass, also called wasting, is referred to as cachexia.

Diarrhea. Diarrhea is frequent, loose, or watery bowel movements. It is a common side effect of certain chemotherapeutic drugs or of radiation therapy to the pelvis, such as in women with uterine, cervical, or ovarian cancers. It can also be caused by certain tumors, such as pancreatic cancer.

Fatigue. Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness, and is the most common problem that people with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously impact family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even impact the will to live.

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin-sometimes unnoticeably-and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, the hair loss is usually temporary, and the hair often grows back.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are common in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer and in some patients receiving radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Nervous system disturbances. Nervous system disturbances can be caused by many different factors, including cancer, cancer treatments, medications, or other disorders. Symptoms that result from a disruption or damage to the nerves caused by cancer treatment (such as surgery, radiation treatment, or chemotherapy) can appear soon after treatment or many years later. See Managing Side Effects: Nervous System Disturbances for the most common symptoms.

Skin problems. The skin is an organ system that contains many nerves. Because of this, skin problems can be very painful. Because the skin is on the outside of the body and visible to others, many patients find skin problems especially difficult to cope with. Because the skin protects the inside of the body from infection, skin problems can often lead to other serious problems. As with other side effects, prevention or early treatment is best. In other cases, treatment and wound care can often improve pain and quality of life. Skin problems can have many different causes, including chemotherapeutic drugs leaking out of the intravenous (IV) tube, which can cause pain or burning; peeling or burned skin caused by radiation therapy; pressure ulcers (bed sores) caused by constant pressure on one area of the body; and pruritus (itching) in patients with cancer, most often caused by leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, or other cancers.

After Treatment

A rehabilitation program after surgery or radiation therapy can be important to help the patient treated for sarcoma regain or maintain optimal limb function. Range-of-motion exercises, strengthening exercises, and a program to reduce limb swelling if present may be prescribed. A formal consultation with a rehabilitation medicine specialist may be extremely important to help optimize the rehabilitation of the patient after treatment. It is worth noting that the majority of patients with a sarcoma in an extremity can be successfully treated and do maintain good limb function.

For some patients, generally those with very large tumors involving the major nerves and blood vessels of the arm or leg, amputation is necessary to control the tumor. This can also be necessary if the tumor grows back in the arm or leg after prior surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy. For these patients, access to prosthetic services (artificial limbs) and mental health support can help manage the adjustment to life following amputation.

Regularly scheduled follow-up visits with the doctors involved in the sarcoma treatment is not only important to detect any possible tumor recurrence, but also help to manage and hopefully prevent some side effects related to treatment. A commonly used follow-up schedule is visits every three to four months for the first three years after treatment, and then every six months until five years after the completion of treatment, and then annually thereafter. Periodic chest x-rays or CT scans will be done to detect possible later spread of cancer to the lungs during these follow-up visits. Imaging of the site of the original tumor with MRI, ultrasound, CT scan, and/or PET scan is also sometimes performed.

The region of the body that received radiation therapy can be at risk for limb swelling, fracture of the thigh or leg bones, reduction in mobility of joints, and fibrosis (hardness) of the soft tissues. Limb swelling can be managed with compression stockings and other special therapies that can be prescribed by doctors. Bone fractures may be prevented by avoiding certain high-impact exercises, which patients should discuss with their doctors. Joint mobility can be improved with a rehabilitation program. Fibrosis may respond to several months of treatment with a combination of vitamin E and pentoxifylline, another oral medication. Skin in the radiation field should be protected from sun exposure with clothing or sunscreen to reduce the chance of a skin cancer developing in that area.