Rhabdomyosarcoma is a type of cancer that begins in a type of muscle called striated muscle. Striated muscles are the skeletal voluntary muscles, which are those muscles that people can control.

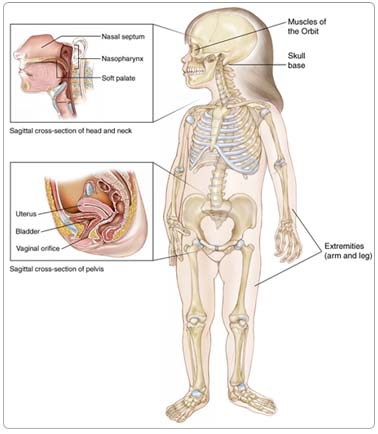

Rhabdomyosarcoma can occur anywhere in the body.

- Head and neck, about 39% (parameningeal sites, 24%; eye orbit, 8%; other head and neck, 7%)

- Urinary or reproductive organs, about 29%

- Arms or legs, about 15%

- Other sites (trunk [torso], intrathoracic, biliary tract, retroperitoneal, pelvic and perineal sites), about 17%

Rhabdomyosarcoma starts from mesenchymal cells, which are immature cells that normally develop to form muscle. Rhabdomyosarcoma tumors are classified into favorable and unfavorable histology subsets, depending on what the cells look like under a microscope. Keep in mind that "favorable" and "unfavorable" tumors refer to the cancer cells, and not the child.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing a disease, including cancer. There are risk factors that can be controlled, such as smoking, and risk factors that cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence disease, for many risk factors it is not known whether they actually cause the disease directly. Some people with several risk factors never develop the disease, while others with no known risk factors do.

Doctors and researchers don't know what causes most childhood cancers. In most cases of rhabdomyosarcoma, there are no clear risk factors.

Children who have the following rare, inherited conditions are at a higher risk for developing rhabdomyosarcoma:

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis

- Costello syndrome

- Cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome

A few cases of rhabdomyosarcoma have been associated with some congenital (present at birth) anomalies (abnormalities). Parental use of cocaine and marijuana prior to a child's birth may increase a child's risk of developing rhabdomyosarcoma.

Symptoms

Children with rhabdomyosarcoma may experience the following symptoms. Sometimes, children with rhabdomyosarcoma do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be similar to symptoms of other medical conditions. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your child's doctor.

Because rhabdomyosarcoma occurs most often in areas that cause noticeable symptoms, it is often diagnosed early. Small, visible, painless lumps often form near the surface of the body, where they are easily spotted. The symptoms of less obvious tumors can vary depending on the part of the body affected.

| Location of Tumor |

Symptom |

| Nasal cavity |

Nosebleed May look like a sinus infection |

| Ears |

Earaches, bleeding, or discharge from the ear canal Mass growing from the ear canal |

| Behind the eye |

May cause the eye to bulge May make the child look cross-eyed |

Bladder, urinary tract, vagina,

or testes |

May cause blood in the urine and make urinating difficult Bleeding from the vagina Mass growing from the vagina Rapid growth around the testicle |

| Abdomen or pelvis |

Abdominal pain Vomiting Constipation |

| Arm or leg muscle |

Mass or growth in the arm or leg |

If the cancer has spread, the child may experience a chronic cough, bone pain, enlarged lymph nodes, weakness, or weight loss.

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has metastasized (spread). Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis. Imaging tests may be used to find out whether the cancer has metastasized. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

The following tests may be used to diagnose rhabdomyosarcoma:

Biopsy. A biopsy removes a small amount of tissue for examination under a microscope. The type of biopsy performed will depend on the location of the cancer. If the tumor is near the surface, the child will be given a local anesthetic during the procedure; if it is deeper inside the body, a general anesthetic will be used.

Immunocytochemistry tests. These are special stains done on the cells taken during the biopsy to help the doctor make an accurate diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma. Special stains that show muscle differentiation, including MyoD-1 and Myogenin, are most helpful.

Genetic tests of tumor tissue. Changes in certain chromosomes (structures that contain the genes in a cell) in the tumor cells, called chromosomal translocations, can help doctors identify the alveolar subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma, although some alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas lack any specific translocation.

Imaging tests

To determine where the cancer is located and if it has spread, the doctor may use the following imaging tests:

X-ray. An x-ray is a picture of the inside of the body. These pictures can help detect tumor growths in the bones or lungs and distortions of soft tissue caused by large tumors.

Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the child's body with an x-ray machine. A computer then combines these images into a detailed, cross-sectional view that shows any abnormalities or tumors. Sometimes, a contrast medium (a special dye) is injected into the patient's vein to provide better detail.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses electromagnetic waves, not x-rays, to produce detailed images of the body. MRIs may create more detailed images than CT scans.

Bone scan. A bone scan can detect whether cancer has spread to the bones. In this procedure, the doctor injects a small amount of radioactive material into the child's vein. The substance collects in the bone and can be detected by a special camera. Normal bone appears gray to the camera, and areas of injury, such as those caused by cancerous cells, appear dark.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan. In a PET scan, radioactive sugar molecules are injected into the body. Cancer cells absorb sugar more quickly than normal cells, so they light up on the PET scan. PET scans are often used to complement information gathered from CT scan, MRI, and physical examination. A PET scan may also be helpful to define the extent of a tumor and may be used to help determine which treatments will work best.

Treatment

Clinical trials are the standard of care for the treatment of children with cancer. In fact, more than 60% of children with cancer are treated as part of a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies that compare the standard treatments (the best treatments available) with newer treatments that may be more effective. Cancer in children is rare, so it can be hard for doctors to plan treatments unless they know what has been most effective in other children. Investigating new treatments involves careful monitoring using scientific methods and all participants are followed closely to track progress.

The Childrens Oncology Group (COG) conducts national clinical trials that are available for children with rhabdomyosarcoma. COG is a National Cancer Institute-supported clinical trials cooperative group devoted exclusively to childhood and adolescent cancer research.

To take advantage of these newer treatments, all children with cancer should be treated at a specialized cancer center. Doctors at these centers have extensive experience in treating children with cancer and have access to the latest research. Many times, a team of doctors treats a child with cancer. Pediatric cancer centers often have extra support services for children and their families, such as nutritionists, social workers, and counselors. Special activities for kids with cancer may also be available.

Children and adolescents with rhabdomyosarcoma require multidisciplinary therapy planning, which means using combinations of chemotherapy, surgery, and, in many situations, radiation therapy. All children with rhabdomyosarcoma require chemotherapy, as well as therapy directed at local control of the tumor (surgery and/or radiation therapy).

Surgery

The goal of surgery is to remove the entire tumor and the margin (healthy tissue around the tumor), leaving a negative margin (no trace of cancer in the healthy tissue). Even children who have tumors that can be completely removed will require chemotherapy. If the tumor cannot be completely removed or is inoperable, the cancer will be treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy to kill the cancer cells. If a tumor is inoperable, a biopsy is still needed to determine the type of tumor.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy travels through the bloodstream to cancer cells throughout the body. Chemotherapy for rhabdomyosarcoma is given by injection into a vein. The drugs that are used most often in North America for rhabdomyosarcoma are vincristine (Oncovin), dactinomycin-D (Actinomycin-D, Cosmegen), and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan). This combination is called VAC.

The new COG low-risk study (started August 2004) evaluates four cycles of VAC followed by vincristine and dactinomycin-D (called VA), attempting to further decrease the total amount of medication given. In addition, for those patients with some tumor remaining after surgery, this study continues the evaluation of a lower dose of radiation therapy.

A recently completed COG intermediate-risk clinical trial tested whether the combination of topotecan (Hycamtin) and cyclophosphamide, added to VAC, improved the treatment's effectiveness. The study results are presently being analyzed.

A new COG intermediate-risk trial will be activated by the beginning of 2007, testing whether the combination of irinotecan (Camptosar) and vincristine, added to VAC, will improve the treatment's effectiveness. In this study, a lower dose of cyclophosphamide will be used in VAC cycles, compared to the previous COG intermediate risk study described above. This study will also evaluate the use of early radiation therapy.

A COG high-risk study was activated in 2006, further evaluating the activity of irinotecan and vincristine as initial therapy, followed by dose compressed therapy with alternating cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide, and ifosfamide (Ifex) and etoposide (VePesid), delivered every two weeks.

To learn more about current COG research studies for rhabdomyosarcoma, visit the COG website.

Because chemotherapy affects normal cells as well as cancer cells, many people experience side effects from treatment. Side effects depend on the drug and the dosage. Common side effects include nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, fatigue, low blood count, bleeding or bruising after minor cuts or injuries, numbness and tingling in the hands or feet, headaches, hair loss, and darkening of the skin and fingernails. Side effects usually go away when treatment is complete.

The most common side effects of VAC therapy are nausea, vomiting, and bone marrow suppression. Although very rare, a few patients may have significant liver damage. Doxorubicin also causes nausea, vomiting, bone marrow suppression, and may cause sores in the mouth. Rarely, this drug affects heart function. Irinotecan may cause loose bowel movements. Common side effects for ifosfamide and etoposide include nausea, vomiting, bone marrow suppression, kidney and central nervous system changes. Intensive therapy used for intermediate- and high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma may cause infertility (the inability to have children).

The medications used to treat cancer are constantly being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications. Learn more about your prescriptions through PLWC's Drug Information Resources, which provides links to searchable drug databases.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to kill cancer cells. The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation therapy given from a machine outside the body. When radiation treatment is given using implants, it is called internal radiation therapy.

Side effects from radiation therapy include fatigue, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements. Most side effects go away soon after treatment is finished.

Recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma

Treatment for recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma (cancer that has come back after treatment) may involve chemotherapy, but it depends on how much of the tumor can be surgically removed, where the cancer recurred, and the treatment the child received previously. Often, new experimental therapies are offered at specialized centers for recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to rhabdomyosarcoma and its treatments.

Diarrhea. Diarrhea is frequent, loose, or watery bowel movements. It is a common side effect of certain chemotherapeutic drugs or of radiation therapy to the pelvis, such as in women with uterine, cervical, or ovarian cancers. It can also be caused by certain tumors, such as pancreatic cancer.

Fatigue (tiredness). Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness, and is the most common problem that people with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously impact family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even impact the will to live.

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin-sometimes unnoticeably-and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, the hair loss is usually temporary, and the hair often grows back.

Infection. An infection occurs when harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi (such as yeast) invade the body and the immune system is not able to destroy them quickly enough. Patients with cancer are more likely to develop infections because both cancer and cancer treatments (particularly chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the bones or extensive areas of the body) can weaken the immune system. Symptoms of infection include fever (temperature of 100.5°F or higher); chills or sweating; sore throat or sores in the mouth; abdominal pain; pain or burning when urinating or frequent urination; diarrhea or sores around the anus; cough or breathlessness; redness, swelling, or pain, particularly around a cut or wound; and unusual vaginal discharge or itching.

Mouth sores (mucositis). Mucositis is an inflammation of the inside of the mouth and throat, leading to painful ulcers and mouth sores. It occurs in up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy treatments. Mucositis can be caused by a chemotherapeutic drug directly, the reduced immunity brought on by chemotherapy, or radiation treatment to the head and neck area.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are common in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer and in some patients receiving radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Skin problems. The skin is an organ system that contains many nerves. Because of this, skin problems can be very painful. Because the skin is on the outside of the body and visible to others, many patients find skin problems especially difficult to cope with. Because the skin protects the inside of the body from infection, skin problems can often lead to other serious problems. As with other side effects, prevention or early treatment is best. In other cases, treatment and wound care can often improve pain and quality of life. Skin problems can have many different causes, including chemotherapeutic drugs leaking out of the intravenous (IV) tube, which can cause pain or burning; peeling or burned skin caused by radiation therapy; pressure ulcers (bed sores) caused by constant pressure on one area of the body; and pruritus (itching) in patients with cancer, most often caused by leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, or other cancers.

After Treatment

After completing therapy, children treated for rhabdomyosarcoma should be monitored for tumor recurrence. Most recurrences develop within the first three years from diagnosis; during this time, routine monitoring should include regular physical examinations and imaging studies (at least every two to six months for the first two years after completing therapy).

Most children treated for rhabdomyosarcoma have received relatively large doses of cyclophosphamide, or similar alkylating agents, and are at risk for damage to the testis (for boys) or ovaries (for girls), causing infertility and other problems. Sites that have received radiation therapy are at risk for growth abnormalities. Bladder dysfunction may occur in children who had bladder or prostate tumors. Children with parameningeal tumors usually receive radiation therapy that can affect the pituitary gland; these children may develop growth hormone deficiency. Children should be routinely monitored for growth patterns, development of sexual maturity, and bladder function. If the eye or mouth was in the radiation field, regular eye examinations and dental examinations are important. Children with extremity (arms or legs) primary tumors may have decreased growth in the affected limb and later limb-length discrepancies. This should be monitored and, if this develops, an evaluation by an orthopedist (bone doctor) is recommended.

Children who have successfully completed therapy for rhabdomyosarcoma may develop second cancers, although this risk is very low. Second cancers may include: bone sarcoma, brain tumor, and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).