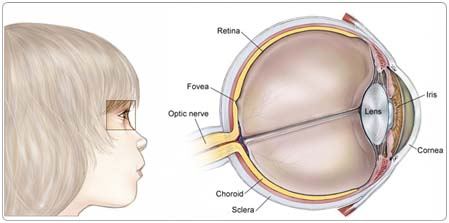

Retinoblastoma is a rare cancer that begins in the part of the eye called the retina. The retina is a thin layer of nerve tissue that coats the back of the eye and enables the eye to see. Most cases are unilateral (involving only one eye), but some may be bilateral (involving both eyes). If retinoblastoma spreads, it can spread to the lymph nodes, bones, or the bone marrow. Rarely, it involves the central nervous system (CNS).

Children may be born with retinoblastoma, but the disease is rarely diagnosed at birth. Most children who begin treatment before the retinoblastoma has spread beyond the eye are cured. An important goal of treatment in children with retinoblastoma is preserving vision.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing a disease, including cancer. There are risk factors that can be controlled, such as smoking, and risk factors that cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence disease, for many risk factors it is not known whether they actually cause the disease directly. Some people with several risk factors never develop the disease, while others with no known risk factors do.

When retinoblastoma affects both eyes, it is always a genetic condition, even though only 10% to 15% of children with retinoblastoma have a family history of the disease. Rarely, the genetic form occurs in only one eye. The genetic form of the disease always occurs in younger children (rarely beyond one year old) and increases the child's risk of developing another cancer later in life. About 60% of children with retinoblastoma do not have the genetic form. They develop a single tumor in only one eye, and there is no increased risk of additional tumors later in life.

Children who have had bilateral retinoblastoma or the hereditary form of unilateral retinoblastoma are at increased risk for developing other types of cancer; the risk of additional tumors is higher in those children who receive radiation therapy to the orbit (eye socket) to preserve vision or to other parts of the body where the tumor has spread.

Symptoms

Children with retinoblastoma often experience the following symptoms. Sometimes, children with retinoblastoma do not show any of these signs or symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be similar to symptoms of other medical conditions. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk to your child's doctor. Sometimes, a doctor finds retinoblastoma on a routine, well-baby examination. Most often, however, parents notice symptoms such as:

- A pupil that looks white or red, instead of the normal black

- A crossed eye (looking either toward the ear or toward the nose)

- Poor vision

- A red, painful-looking eye

- An enlarged pupil

- Different-colored irises

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has metastasized (spread). Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. Although a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis for most types of cancer, this is usually not possible in the case of retinoblastoma, and the doctor will suggest other ways to make a diagnosis. Imaging tests may be used to find out whether the cancer has metastasized. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

The next step after observing the symptoms is to have the child examined by a specialist, who will do a thorough ophthalmic examination to check the retina for a tumor. Depending on the age of the child, either a local or general anesthetic is used during the eye examination.

The specialist will make a drawing or take a photograph of the tumor in the eye to provide a record for future examinations and treatment, and may use additional tests to confirm or detect a tumor.

If a newborn has a family history of retinoblastoma, the baby should be examined shortly after birth by an ophthalmologist (a medical eye doctor) who specializes in cancers of the eye.

The following tests may be used to diagnose retinoblastoma:

Ultrasound. An ultrasound finds tumors in the child's body using sound waves. A transmitter that emits sound waves is moved over the child's body. Tumors generate different echoes of the sound waves than normal tissue does, so when the waves are bounced back to a computer and changed into images, the doctor can locate masses inside the body. The procedure is painless.

Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the child's body with an x-ray machine. A computer then combines these images into a detailed, cross-sectional view that shows any abnormalities or tumors. Sometimes, a contrast medium (a special dye) is injected into a vein to provide better detail. A CT scan helps the doctor find cancer outside of the eye.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses magnetic fields, not x-rays, to create computer-generated pictures of the brain and spinal column. MRIs may create more detailed pictures than CT scans and provide the specialist with a picture of the inside of the eye and the brain.

MRI or CT scan of the brain. These tests may be recommended to determine if there is an abnormality of the pineal gland (a small gland in the brain). It is recommended that these scans be performed once every six months until the age of five in children with the genetic form of retinoblastoma (those with bilateral disease and those with unilateral disease with a family history of the disease). Very young children with a tumor in one eye who do not have a family history of the disease may also be at risk, and these tests may be recommended. Scans may also be recommended years after treatment for children who have received external-beam radiation therapy, either as a baseline in the event that problems arise, or to determine the cause of a symptom or sign.

Children who are diagnosed with retinoblastoma will require a complete physical examination. If there are any additional symptoms or abnormal findings, children may also undergo additional tests to determine if the cancer has spread elsewhere in the body.

Blood tests. These tests evaluate the blood and check for problems with the liver and kidneys. The doctor may also look at the blood for changes in chromosome 13. Chromosomes are the part of the cell that contains genes, and in a few cases of retinoblastoma, these genes are either missing or nonfunctional. Molecular analysis of the gene is now possible in a few institutions to determine changes that are not visible on ordinary chromosome analysis.

Lumbar puncture (spinal tap). In this test, a small amount of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is removed with a needle from the child's back and examined under a microscope to detect cancer cells.

Bone marrow aspiration. This procedure is performed to determine if any retinoblastoma cells have spread to the marrow. For this test, a small amount of bone marrow is removed from the hip with a needle and examined under a microscope.

Hearing test. Children with retinoblastoma taking certain chemotherapy drugs may have their hearing tested (audiology test) to make sure the drugs are not causing hearing loss.

Treatment

Clinical trials are the standard of care for the treatment of children with cancer. In fact, more than 60% of children with cancer are treated as part of a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies that compare the standard treatments (the best treatments available) with newer treatments that may be more effective. Cancer in children is rare, so it can be hard for doctors to plan treatments unless they know what has been most effective in other children. Investigating new treatments involves careful monitoring using scientific methods and all participants are followed closely to track progress.

To take advantage of these newer treatments, all children with cancer should be treated at a specialized cancer center. Doctors at these centers have extensive experience in treating children with cancer and have access to the latest research. Many times, a team of doctors treats a child with cancer. Pediatric cancer centers often have extra support services for children and their families, such as nutritionists, social workers, and counselors. Special activities for children with cancer may also be available. Surgical treatment for retinblastoma should also be performed by specially trained pediatric ophthalmologists.

Several types of therapies are used for retinoblastoma, and more than 90% of children can be cured. In addition to cure, an important goal of therapy for retinoblastoma is the preservation of vision. Many of these treatment approaches have become available as a result of clinical trials. The Childrens Oncology Group has recently developed treatment protocols for which some children with retinoblastoma will be eligible.

Treatments for retinoblastoma include:

Surgery

Surgery to remove the eye is called enucleation. Children with a tumor in one eye only can often be cured with this treatment. In children with a tumor in both eyes, enucleation is used only if the ocular oncologist determines that preserving vision using other treatment is not possible.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other particles to kill cancer cells. The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation therapy given from a machine outside the body. Radioactive plaque therapy, also called internal radiation therapy, is the delivery of radiation therapy directly to the eye with a disc containing radiation.

Fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, and headache are common temporary side effects of radiation therapy. Radiation therapy in young children can interfere with normal growth, including growth of the orbital bones, depending on the dose. The increased risk of additional tumors later in life for children with the hereditary form of retinoblastoma is further increased following radiation therapy. These effects are not seen after radioactive plaque therapy.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy uses extreme cold to destroy cancer cells.

Laser therapy

Laser therapy uses heat in the form of a laser to shrink smaller tumors. It may be called thermotherapy (or TTT for transpupillary thermotherapy), and it may be used alone or in addition to cryotherapy or radiation therapy. Photocoagulation is a different type of laser therapy that uses light to shrink tumors.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells, and may be used to shrink tumors in the eye. It is administered by a pediatric oncologist and often makes it possible to completely eliminate any remaining smaller tumors with the following focal (localized) measures:

- Thermotherapy or photocoagulation (laser therapy)

- Cryotherapy

- Radioactive plaque therapy

Chemoreduction is a treatment approach that is often used in children with bilateral disease in the hope of avoiding enucleation and preserving vision in at least one eye. The ophthalmologist, in consultation with the pediatric oncologist, will determine if this treatment is appropriate. Both doctors will monitor the response to treatment regularly and may recommend additional treatment to prevent the cancer from returning.

The drugs used most often are vincristine (Oncovin), carboplatin (Paraplatin), and etoposide (VePesid, Etopophos, Toposar). Depending on the extent of the tumor, a combination of two or more drugs will be recommended. All chemotherapy has side effects that occur during the period of treatment. Some drugs have the potential for specific long-term complications. Your doctor will discuss these before treatment begins.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your child's doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications they've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

Recurrent retinoblastoma

Treatment of recurrent retinoblastoma depends on where the cancer recurred and how aggressive the new tumor is. The doctor may recommend surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or focal measures (photocoagulation, thermotherapy, or cryotherapy).

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to retinoblastoma and its treatments.

Fatigue (tiredness). Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness, and is the most common problem that people with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously impact family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even impact the will to live.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are common in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer and in some patients receiving radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

After Treatment

All children cured of cancer, including those with retinoblastoma, require life-long, follow-up care. Once a child has been free of retinoblastoma for two to four years following treatment, and is considered cured, the emphasis during periodic follow-up visits changes. Pediatric oncologists will focus on the quality of the child's life, including developmental and psychosocial concerns.

Most young children adapt well to the loss of one eye if enucleation took place. Rarely, both eyes will require removal to save the child's life. If both eyes are removed, the local educational system is required to provide special services. Parents are encouraged to investigate the school's services and advocate on their child's behalf.

Based on the therapy the child received and whether the child has the genetic form of retinoblastoma, the doctor will determine what evaluations are needed to check for long-term effects. This may include imaging studies (CT scan or MRI) and blood work. Counseling will also be provided in the case of children who have an increased risk of additional tumors later in life, such as those with bilateral disease and those with unilateral disease who have a family history of the disease. Annual visits to specialized ophthalmologic and medical oncologists are necessary in order to fully monitor the child's recovery, and to increase the probability that a second cancer will be detected in its earliest stages.

Children who have had cancer can also enhance the quality of their future by following established guidelines for good health into and through adulthood, including not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoiding drinking alcohol in excess.