Overview

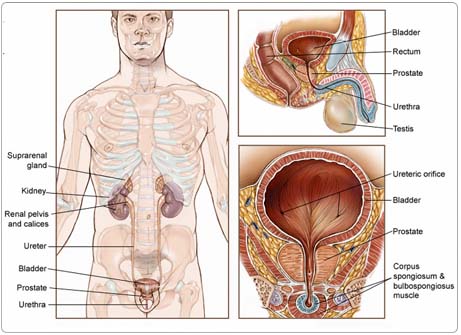

Prostate cancer is a malignant tumor that begins in the prostate gland of men. The prostate is a walnut-sized gland located behind the base of the penis, in front of the rectum and below the bladder. It surrounds the urethra, the tube-like channel that carries urine and semen through the penis. The prostate's main function is to produce seminal fluid, the liquid in semen that protects, supports, and helps transport sperm.

Cancer develops when changes occur in DNA, the genetic material containing "instructions for growth and development" for all types of cells. When DNA is altered, normal cells may multiple without control or order, and tumors can form.

Some prostate cancers grow very slowly and may not cause problems for years. Many men with slow-growing prostate cancer do not die from prostate cancer, but rather live with their disease. In this situation, the cause of death is usually not from prostate cancer, but other causes. However, if cancer does spread quickly to other parts of the body, treatment can help eliminate the cancer and also control pain, fatigue, and other symptoms and prolong life. Prostate cancer is somewhat unusual from other types of cancer, in that many patients with very advanced, metastatic cancer will respond to treatment and survive in excellent health for many years.

More than 95% of prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas, cancers that develop in glandular tissue. A rare type of prostate cancer known as neuro-endocrine or small cell anaplastic cancer tends to metastasize (spread) earlier, but usually does not produce prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a tumor marker discussed below.

Risk Factors and Prevention

A risk factor is anything that increases a persons chance of developing a disease, including cancer. There are risk factors that can be controlled, such as smoking, and risk factors that cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence disease, for many risk factors it is not known whether they actually cause the disease directly. Some people with several risk factors never develop the disease, while others with no known risk factors do. However, knowing your risk factors and communicating them to your doctor may help you make more informed lifestyle and health-care choices.

Since the exact cause of prostate cancer is still unknown, it is also unknown how to prevent prostate cancer. The following factors can raise a persons risk of developing prostate cancer:

Age. The risk of prostate cancer increases with age, rising rapidly after age 50. More than 80% of prostate cancers are diagnosed in men who are 65 years old or older.

Race/ethnicity. Black men are at higher risk for prostate cancer than white men. They are more likely to develop prostate cancer at an earlier age and to have aggressive, fast-growing tumors. Prostate cancer occurs most often in North America and northern Europe and is less common in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Of importance, it appears that its frequency is increasing in Asian populations living in urbanized environments, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and North American/European cities.

Family history. A man who has a father or brother with prostate cancer has a higher risk of developing the disease than a man who does not. Researchers have discovered specific genes that may possibly be associated with prostate cancer, although these have not yet been shown to cause prostate cancer or to be specific to this disease.

Diet. No study has shown conclusively that diet can directly influence the development of prostate cancer, but many studies have indicated there may be a link. There is not enough information yet to make clear recommendations about the role diet plays in prostate cancer, but the following may be helpful:

- A diet high in fat, especially animal fat, may increase prostate cancer risk. In fact, many doctors believe that a low-fat diet may help to reduce the risk of prostate cancer.

- A diet high in vegetables, fruits, and legumes (beans and peas) may decrease risk of prostate cancer. It is unclear which nutrients are directly responsible, but lycopene, found in tomatoes and other vegetables, may slow or prevent cancer growth. A low-fat diet that is high in vegetables and fruits can lower blood pressure and the risk of heart disease, with no evidence that such a diet causes harm.

- Selenium, an element humans get in trace amounts from food and water, may play a role in lowering the risk of prostate and other cancers. Selenium is currently being tested in clinical trials and has not yet been proven to alter risk.

- It has been suggested that vitamin E may help to reduce the risk of prostate cancer; this is currently being tested in clinical trials and has not yet been proven to alter risk. In some studies of vitamin E in other settings, it has been suggested that there may be inherent cardiovascular risks (for example, an increased chance of having cardiac or blood vessel problems) with the use of high doses of vitamin E, and final judgment on the use of this supplement will require the completion of ongoing clinical trials.

Hormones. High levels of testosterone (a male sex hormone) may speed up or cause the development of prostate cancer. Prostate cancer does not develop in men who, for other reasons, were castrated (the removal of the testes) before puberty and whose bodies no longer make testosterone. Stopping the bodys production of testosterone, called androgen deprivation therapy, or castration, often treats advanced prostate cancer.

Symptoms

Often, prostate cancer is discovered through a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or digital rectal examination (DRE) in otherwise healthy men who have not had any symptoms. (Both tests are described in Diagnosis.) When prostate cancer does cause symptoms, the following symptoms may occur. Sometimes, people with prostate cancer do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be caused a medical condition that is not cancer. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your doctor.

- Frequent urination

- Pain or burning during urination

- Weak or interrupted urine flow

- Blood in the urine

- The urge to urinate frequently at night

None of these symptoms is specific to prostate cancer. The same symptoms occur in men who have a noncancerous condition known as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), or enlarged prostate. Urinary symptoms also can indicate an infection or other conditions.

If cancer has spread beyond the prostate gland, a man may experience:

- Pain in the back, hips, thighs, shoulders, or other bones

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fatigue

- Other symptoms that arise at the site of cancer growth

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has metastasized. Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis; this occurs very infrequently with prostate cancer. For example, this occurs when a patient has another medical problem, thus making it difficult to carry out a biopsy, and it occurs when a patient has a very high PSA and a positive bone scan. Imaging tests may be used to find out whether the cancer has metastasized. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

The earlier prostate cancer is detected, the more likely it can be cured. Two tests are now commonly used to detect prostate cancer in men: the PSA test and the DRE.

A note about the prostate cancer screening controversy

There is some controversy about using the PSA test as a screening test with large numbers of men with no symptoms of prostate cancer. The PSA test is useful for detecting early prostate cancer, but it has not yet proven to lower death rates. It also detects conditions that are not cancer, and misses some prostate cancers.

Unlike other cancers, prostate cancer grows slowly in many men-so slowly that in some men it would not threaten the life even if not treated. Because of this, detecting prostate cancer may mean that some men have surgery and other treatments that may not ever be needed. For this reason, many men and their doctors may consider active surveillance (also called watchful waiting) of their cancer rather than immediate treatment. This option may be best suited for those with very small, low-grade cancers detected on extended biopsies and perhaps those men who may be much older or suffer from other life-threatening or life-limiting medical illnesses. Since prostate cancer treatments have significant side effects, treating it unnecessarily can seriously affect a man's quality of life. However, it is important to note that it is not easy to predict which tumors will behave aggressively and which will grow slowly. This has led some doctors to believe that it is safer to use screening tests to detect aggressive cases early even if it means that some patients will receive unnecessary treatment for slow-growing cases of prostate cancer. This is particularly the case as many of the initial screening tests, such as DRE or measurement of PSA, are not dangerous. A major study on the use of prostate screening is under way in Europe, and this may cast important light on this complex debate. This issue remains controversial.

Until there is more complete research to evaluate this issue, ASCO does not yet have an official statement about prostate cancer screening or recommendations for men regarding when they should begin testing for prostate cancer. Every patient should discuss his individual situation with his doctor and work together to make a decision.

Diagnosing prostate cancer

In addition to a physical examination, the following tests may be used to diagnose prostate cancer:

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. Prostate-specific antigen is a substance (a type of protein released by prostate tissue) found in higher levels in a man's blood when there is abnormal activity in the prostate, including prostate cancer, BPH, or prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate). A PSA test detects higher than normal levels of PSA that can indicate the presence of prostate cancer. As noted above, the PSA test is very sensitive, meaning that most patients with cancer will have an elevated level, but the test is not specific in that elevated PSA levels can be from noncancer causes. Doctors can look at features of the PSA value, such as absolute level, change over time, and level in relation to prostate size, to determine if a biopsy is warranted. In addition, a version of the PSA test allows the doctor to measure a specific component, called the "free" PSA, which can sometimes help determine if a tumor is benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous).

Digital rectal examination (DRE). A doctor inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into a man's rectum and feels the surface of the prostate for any irregularities. This test is not very sensitive; thus, most men with early prostate cancer have normal DREs.

If the PSA or DRE test results are abnormal, the following tests can confirm a diagnosis of cancer:

Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS). A doctor inserts a probe into the rectum and takes a picture of the prostate using sound waves that bounce off the prostate.

Biopsy. The only way to be sure of a cancer diagnosis is with a biopsy. A biopsy is the removal of a small amount of tissue for examination under a microscope. To get a tissue sample, most often a surgeon uses TRUS and a biopsy tool to take very small slivers of prostate tissue. This procedure is usually performed as an outpatient procedure, under local anesthesia.

To determine if cancer has spread beyond the prostate, doctors may perform the following imaging tests:

Bone scan. A bone scan uses a radioactive tracer to look at the inside of the bones. The tracer is injected into a patients vein. It collects in areas of the bone and is detected by a special camera. Healthy bone appears gray to the camera, and areas of injury, such as those caused by cancer, appear dark.

Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body with an x-ray machine. A computer then combines these images into a detailed, cross-sectional view that shows any abnormalities or tumors.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses magnetic fields, not x-rays, to produce detailed images of the body.

Treatment

The treatment of prostate cancer depends on the size and location of the tumor, whether the cancer has spread, and the persons overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan.

Active surveillance (watchful waiting), for early-stage cancers

If a prostate cancer is in an early stage, is slow-growing, and if treating the cancer would cause more discomfort than the disease itself, a doctor may recommend watchful waiting, also called active surveillance. The cancer is monitored closely, and treatment would begin only when the tumor shows signs of becoming more aggressive or spreading. This approach may be taken in much older patients or in those with other serious or life-threatening illnesses. However, real caution must be taken not to make errors of judgment, under-estimate the severity of the prostate cancer, or over-estimate the severity of the other illnesses. In other words, doctors must collect as much information as possible about the patients other illnesses and potential life expectancy, so they don't miss the chance to detect an early, aggressive prostate cancer. New information is becoming available all the time, and it is important for the patient to discuss these issues carefully with a specialist in this field to obtain current information.

Surgery

Surgery is used to try to cure cancer before it has spread outside the prostate. The type of surgery depends on the stage of the disease, the patients general health, and other factors.

Radical prostatectomy. A radical prostatectomy involves surgical removal of the whole prostate and accompanying seminal vesicles and possibly lymph nodes in the pelvic area. This operation has the risk of interfering with sexual potency. Nerve-sparing surgery, when possible, increases the chances that a man will remain sexually potent after surgery by avoiding surgical damage to the nerves that allow erections and orgasm to occur. Orgasm can occur even if nerves are cut; these are two separate processes. Urinary incontinence (inability to control urine flow) is also a possible complication of prostatectomy. To help resume normal sexual function, men can receive drugs, such as sildenafil citrate (Viagra) and several similar, newer drugs, penile implants, or injections. Sometimes, additional surgery can fix the complication of urinary incontinence.

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). TURP is most often used to relieve symptoms of urinary obstruction, not to cure cancer. In this procedure, under a full anesthetic, a surgeon inserts a cystoscope (a narrow tube with a cutting device) into the urethra and into the prostate to remove prostate tissue. This is rarely used as an anticancer procedure in current clinical practice.

Cryosurgery. Most commonly used in experimental studies, cryosurgery (also called cryotherapy or cryoablation) involves freezing cancer cells with a metal probe inserted through a small incision in the area between the rectum and the scrotum, the skin sac that contains the testicles. Cryosurgery may be useful for early-stage cancers and for men who cannot have a radical prostatectomy. Some doctors view cryotherapy as experimental and have concerns about complications, which can include the development of fistulae (holes between the prostate and the bowel), although this complication appears to occur much less frequently with the development of newer cryosurgery techniques.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays to destroy cancer cells. Radiation therapy may be given externally, called external-beam radiation therapy, where a machine uses high-energy rays to damage cancer cells, or internally, where a radioactive substance or seeds are placed inside the prostate, near the tumor. Radiation therapy can be useful at all stages of localized cancer, either to try to cure the disease. Also, it is used as a method of relieving symptoms, such as pain in patients with advanced or metastatic cancer. Several treatments or "fractions" may be needed.

External-beam radiation therapy. External-beam radiation therapy focuses a beam of radiation on the area affected by cancer. Some cancer centers use conformal radiation therapy (CRT), where computers help precisely map the location and shape of the cancer. CRT reduces radiation exposure to healthy tissues and organs around the tumor by directing the radiation therapy beam from different directions with the intention of focusing the dose on the area of the tumor.

Brachytherapy. Brachytherapy involves insertion of radioactive sources directly into the prostate. These give off localized radiation and may be used for hours (high dose rate) or for weeks (low dose rate). Low dose rate seeds are left in the prostate permanently, after all the radioactive material has been used up.

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). IMRT is a form of three-dimensional (3-D) CRT. Conformal radiation therapy uses CT scans to form a 3-D picture of the prostate before treatment. In IMRT, the radiation beams vary in strength at different points in the beam and are aimed at a tumor from many angles, enabling the treatment of complex shapes. The doses of radiation treatment are precise enough to avoid damaging healthy tissue around the prostate.

Radiation therapy may cause the following side effects:

- Diarrhea or other disruption of bowel function

- Increased urinary urge or frequency

- Fatigue

- Impotence (inability to get an erection)

- Rectal discomfort, burning, or pain

Hormone therapy

Since prostate cancer growth is driven by male sex hormones known as androgens, reducing levels of these hormones can help slow the growth of the cancer. Hormone treatment is also called androgen ablation or androgen deprivation therapy. The most common androgen is testosterone. The production of testosterone can be reduced either surgically, with surgical castration, or through the use of drugs that turn off the function of the testicles (see below).

Hormone therapy is used to treat prostate cancer that has continued to grow after surgery and radiation therapy or when it is widespread at the time of diagnosis. More recently, hormone therapy has also been used in conjunction with radiation therapy in patients with certain disease features that place them at a higher risk for recurrence. In some instances, initial hormone therapy will be used to shrink a prostate cancer prior to the use of radiation therapy or surgery. In some patients with locally extensive tumors identified during a radical prostatectomy, hormones will be given after the surgery for two to three years as adjuvant therapy (treatment that is given after the first treatment).

Traditionally, hormone therapy was used until it stopped controlling the cancer. Then the cancer was said to be hormone refractory (hormone therapy stops working), and other options were considered. Recently, researchers have begun studying intermittent hormone therapy, which is hormone therapy that is given for specified periods and then discontinued temporarily according to a schedule. Giving hormones in this way appears to reduce the symptoms of this therapy. In addition, intermittent hormone therapy may possibly maintain hormone responsiveness for a longer period of time than standard (continuous) hormone treatment; this concept is currently being tested in clinical trials.

Types of hormone therapy

Bilateral orchiectomy. Bilateral orchiectomy involves surgical removal of the testicles. Even though this is surgery, it is called a hormone treatment because it removes the main source of testosterone production, the testicles.

LHRH agonists. LHRH stands for luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. LHRH agonists reduce the body's production of testosterone by interfering with hormonal control mechanisms within the brain, which control the functioning of the testicles.

Anti-androgens. While LHRH agonists lower testosterone levels in the blood, anti-androgens block testosterone from binding to so-called "androgen receptors, chemical structures in the cancer cells that allow testosterone and other male hormones to enter the cells.

Female hormones. Estrogen can lower testosterone levels. When this drug is given as a pill, side effects can include heart problems and blood clots. More recently, estrogens have been administered as injections or as skin patches, and this type of treatment may be associated with a lower chance of heart and clotting side effects.

Combined androgen blockade. Sometimes, LHRH agonists are used in combination with peripheral-blocking drugs, such as anti-androgens, to more completely inhibit male hormones. Many doctors feel that this combined approach is the safest way to start hormone treatment, as this protects from a potential flare-up or increase in activity of the prostate cancer cells that sometimes occurs as a result of a temporary surge in testosterone production by the testicles (in response to the LHRH agonists). Major clinical trials have not shown a big difference in long-term survival results from the use of combined androgen blockade as permanent therapy; therefore, some doctors prefer to give combined drug treatment only for the first two to three months. This latter approach has not been validated in clinical trials.

Hormone therapy may cause significant side effects. Side effects generally go away after hormone treatment is finished, except in men who have had an orchiectomy. Patients may experience:

- Impotence (inability to get erections)

- Loss of libido (sexual desire)

- Hot flashes

- Gynecomastia (enlarged breasts)

- Osteoporosis (weakening bones)

Patients who have received LHRH agonists for more than two years will frequently have ongoing hormonal effects, even if the drugs are no longer given.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy can be taken orally (by mouth) or intravenously, and it may help patients with advanced or hormone-refractory prostate cancer. There is no standard chemotherapy for use against prostate cancer, but a number of clinical trials are exploring chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer. The most popular, current approach involves the use of a drug called docetaxel (Taxotere) given in conjunction with a steroid called prednisone. This combination has been shown to make men with advanced prostate cancer live longer than another chemotherapy, mitoxantrone (Novantrone), which is most useful for controlling prostate cancer symptoms.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

Advanced prostate cancer

Some prostate cancers develop the ability to grow without the presence of male sex hormones, and hormone treatments stop working. This is called androgen-independent cancer, or hormone-refractory prostate cancer, and there is no cure. In these cases, radiation therapy or chemotherapy may be able to offer significant benefit for patients.

If all treatments have failed to control prostate cancer, or if cancer comes back after treatment, a patient may experience pain, fatigue, and weight loss. At this point, the goal of treatment switches from curing the cancer to slowing it down and relieving symptoms.

It is important to note that many men outlive their prostate cancer, even those with advanced disease. Unlike some other cancers, many men with advanced prostate cancer can expect to live for many years. Often, the prostate cancer grows slowly, and there are now some effective treatment options that extend life even further. A few drugs can help treat the symptoms of advanced cancer.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy (see above). Chemotherapy is most commonly used for patients with advanced hormone-refractory prostate cancer. It can be effective in relieving symptoms, such as pain, weight loss, and fatigue, and may prolong life in patients who respond to this treatment.

Strontium and samarium. Given by injection, these are radioactive agents that are absorbed near the area of bone pain. The radiation that is released helps relieve the pain, probably by causing local tumor shrinkage.

Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronic acid (Zometa). Given by injection, these drugs reduce the level of calcium in the blood and also cause a reduction of bone complications (such as pain, fracture, need for surgery) due to metastases. A high calcium level is called hypercalcemia and is sometimes present in advanced prostate cancer.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to prostate cancer and its treatments.

Diarrhea. Diarrhea is frequent, loose, or watery bowel movements. It is a common side effect of certain chemotherapeutic drugs or of radiation therapy to the pelvis, such as in women with uterine, cervical, or ovarian cancers. It can also be caused by certain tumors, such as pancreatic cancer.

Fatigue (tiredness). Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness and is the most common problem patients with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously affect family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even affect the will to live.

Hormone deprivation symptoms in men. Many men who experience a halt in their hormone levels because of prostate cancer treatment (particularly those treatments that stop the production of testosterone, such as removal of the testicles or androgen ablation [hormone treatment]) experience symptoms, such as hot flashes, osteoporosis (loss of bone mass that makes bones break and fracture easily), decreased libido (desire for sex), erectile dysfunction (problems with erections), fatigue, and depression or irritability, that are caused by the body's lack of testosterone. These symptoms may occur in men without prostate cancer also, as part of the aging process. In men without prostate cancer, treatments to raise testosterone levels can help relieve these symptoms. Since testosterone helps prostate cancer grow, this is not an option for men with prostate cancer.

Sexual dysfunction. Sexual dysfunction is common in all people, affecting up to 43% of women and 31% of men. It may be even more common in patients with cancer, as a result of treatments, the tumor, or stress. Many people, with or without cancer, find it intimidating to discuss sexual problems with their doctors. Sexual problems are most commonly caused by body changes from cancer surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy, hormone changes, fatigue, pain, nausea and/or vomiting, medications that reduce libido (desire for sex), fear of recurrence, stress, depression, and anxiety. Symptoms of sexual dysfunction generally fall into four categories: desire disorders, arousal disorders, orgasmic disorders, and pain disorders.

After Treatment

After treatment for prostate cancer ends, talk with your doctor about developing a follow-up care plan. This plan may include regular physical examinations and/or medical tests to monitor your recovery for the coming months and years.

People recovering from prostate cancer are encouraged to follow established guidelines for good health, such as maintaining a healthy weight, eating a balanced diet, and having recommended cancer screening tests. Talk with your doctor to develop a plan that is best for your needs. Moderate physical activity can help rebuild your strength and energy level. Your doctor can help you create an appropriate exercise plan based upon your needs, physical abilities, and fitness level.