Overview

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is a term that refers to several, very different types of lymphoma, a cancer of the lymph system. When lymphatic cells mutate (change) and grow unregulated by the processes that normally decide cell growth and death, they can form tumors.

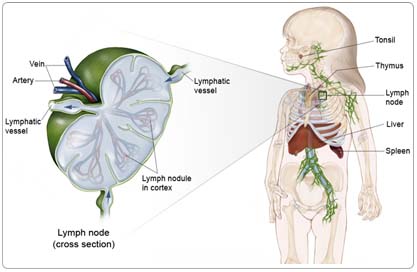

The lymph system is made up of thin tubes that branch out to all parts of the body. Its job is to fight infection and disease. The lymph system carries lymph, a colorless fluid containing lymphocytes (white blood cells). Lymphocytes fight germs in the body. B-lymphocytes (also called B-cells) make antibodies to fight bacteria, and T-lymphocytes (also called T-cells) kill viruses and foreign cells and trigger the B-cells to make antibodies.

Groups of bean-shaped organs called lymph nodes are located throughout the body at different sites in the lymph system. Lymph nodes are found in clusters in the abdomen, groin, pelvis, underarms, and neck. Other parts of the lymph system include the spleen, which makes lymphocytes and filters blood; the thymus, an organ under the breastbone; and the tonsils, located in the throat.

Because lymph tissue is found in so many parts of the body, non-Hodgkin lymphoma can start almost anywhere and can spread to almost any organ in the body. It most often begins in the lymph nodes, liver, or spleen, but can also involve the stomach, intestines, skin, thyroid gland, or any other part of the body.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing a disease, including cancer. There are risk factors that can be controlled, such as smoking, and risk factors that cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence disease, for many risk factors it is not known whether they actually cause the disease directly. Some people with several risk factors never develop the disease, while others with no known risk factors do.

Although the exact cause of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is unknown, some children seem to have a slightly greater risk of developing the disease:

- Those who have had illnesses related to the Epstein-Barr virus (for example, infectious mononucleosis)

- Those who have acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)

- Children who have received an organ transplantation

- Children born with deficiencies in their immune systems

- Children who have been treated with certain drugs for other cancers

- In rare cases, children who take dilantin, an antiseizure drug

Symptoms

Children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma often experience the following symptoms. Sometimes, children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be similar to symptoms of other medical conditions. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your child's doctor.

The symptoms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma may vary depending on where the cancer develops and what organ is involved.

General symptoms may include:

- Swelling or lumps in the lymph nodes in the abdomen, groin, neck, or underarm

- Fever that is not associated with an illness

- Weight loss

- Sweating and chills

- Extreme fatigue (tiredness)

Symptoms related to tumor location may include:

- A distended belly, caused by a large tumor in the abdomen

- Painful urination and bowel movements, caused by fluid accumulation and a tumor around the kidneys and intestines

- Difficulty breathing, caused by a tumor in the thymus near the windpipe

A serious symptom of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS). In SVCS, a tumor in the thymus area behind the breastbone squeezes the vein that carries blood from the head and arms to the heart. The head and arms swell as a result. SVCS can affect the brain and is life threatening. Children with SVCS need emergency medical attention.

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has metastasized (spread). Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis. Imaging tests may be used to find out whether the cancer has metastasized. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

The doctor will first perform a physical examination and take a complete medical history to determine if a person has non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The following tests may be used to diagnose non-Hodgkin lymphoma:

Biopsy. A biopsy removes a small amount of tissue for examination under a microscope. Other tests can suggest that cancer is present, but only a biopsy can make a definite diagnosis. If the tumor is near the surface, the child will be given a local anesthetic to numb the area. If it is deeper inside the body, the doctor will use a general anesthetic. The doctor may also perform a fine-needle aspiration biopsy, in which a thin needle attached to a syringe is used to remove some fluid and tissue from a tumor.

Bone marrow aspiration. To determine whether the cancer has spread, the doctor may do a bone marrow aspiration. In this test, a small amount of bone marrow is removed and examined under a microscope. The child's skin is numbed with a local anesthetic.

Lumbar puncture (spinal tap). A lumbar puncture is a procedure in which a doctor takes a sample of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) to look for cancer cells, blood, or tumor markers (substances found in higher than normal amounts in the blood, urine, or body tissues of people with certain types of cancer). CSF is the fluid that flows around the brain and the spinal cord. The child will receive an anesthetic to numb the lower back before the procedure.

Cytogenetic analysis. A pathologist (a doctor who specializes in interpreting laboratory tests and diagnosing disease) may examine the pairs of chromosomes (strings of DNA that contain genes) from the biopsy under the microscope to check for chromosomal abnormalities. This helps the doctor identify the subtype of lymphoma and plan treatment.

Flow cytometry and immunocytochemistry. To determine the subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the doctor may do two tests: flow cytometry and immunocytochemistry. A flow cytometry involves cells of interest being removed and treated with a fluorescent, dye-equipped antibody that attaches to DNA. The cells are then passed in front of a laser beam, which allows a special computer to measure their DNA level. Higher amounts of DNA than normal may indicate cancer. During an immunocytochemistry test, fluorescent antibodies or immunoperoxidase staining may be used to determine the subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Imaging tests

To determine where the cancer is and if it has spread, the doctor may use the following imaging tests:

Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the child's body with an x-ray machine. A computer then combines these images into a detailed, cross-sectional view that shows any abnormalities or tumors. Sometimes, a contrast medium (a special dye) is injected into a vein to provide better detail. CT scans of the chest and abdomen can help find cancer that has spread to the lungs, lymph nodes, and liver.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses magnetic fields, not x-rays, to produce detailed images of the brain and spinal column. MRIs may create more detailed pictures than CT scans.

X-ray. An x-ray is a picture of the inside of the body. For instance, a chest x-ray can help doctors determine if the cancer has spread to the lungs.

Bone scan. A bone scan can detect injuries to the bones, which could be caused by cancer. In this procedure, the doctor injects a small amount of radioactive material into the child's vein. The substance collects in the bone and can be detected by a special camera. Normal bone appears gray and areas of injury, such as those caused by cancerous cells, appear dark to the camera.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) scan. A PET scan is a test that creates an image of the body using an injection of a substance, such as glucose (sugar), in a low dose, radioactive form to determine the metabolic activity in cells. It can show the difference between benign (noncancerous) shadows and malignancies (cancerous) that may not be clear on a CT scan or MRI. The exact accuracy and role of PET scanning in non-Hodgkin lymphoma is not yet clear, although lymphoma-containing masses often show up on PET scans. In the future, a PET scan may help determine the success of treatment for patients with aggressive types of lymphoma.

Treatment

The treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma depends on the size and location of the tumor, whether the cancer has spread, and the child's overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan.

Clinical trials are the standard of care for the treatment of children with cancer. In fact, more than 60% of children with cancer are treated as part of a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies that compare the best treatments available (standard treatments) with newer treatments that may be more effective. Cancer in children is rare, so it can be hard for doctors to plan treatments unless they know what has been most effective in other children. Investigating new treatments involves careful monitoring using scientific methods and all participants are followed closely to track progress.

To take advantage of these newer treatments, all children with cancer should be treated at a specialized cancer center. Doctors at these centers have extensive experience in treating children with cancer and have access to the latest research. Many times, a team of doctors treats children with cancer. Pediatric cancer centers often have extra support services for children and their families, such as nutritionists, social workers, and counselors. Special activities for kids with cancer may also be available.

Three types of therapy are used to treat non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children: chemotherapy, radiation treatment, and bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Sometimes, the treatments are used in combination.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy travels through the bloodstream to cancer cells throughout the body. Chemotherapy is the primary treatment for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and may be given by mouth, injected into a vein or muscle, or injected into the cerebral spinal fluid.

The type of chemotherapy used depends on the cancer's stage (how far advanced the cancer is) and the type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Because chemotherapy attacks rapidly dividing cells, including those in normal tissues such as the hair, lining of the mouth, intestines, and bone marrow, children receiving chemotherapy may lose their hair, develop mouth sores, or have nausea and vomiting. In addition, chemotherapy may lower the body's resistance to infection, lead to increased bruising and bleeding, and cause fatigue. These side effects can be controlled during treatment and usually go away after chemotherapy is completed. The severity of the side effects depends on the type and amount of the drug being given and the length of time the child receives the drug.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your child's doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications they've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications. Learn more about your child's prescriptions through PLWC's Drug Information Resources, which provides links to searchable drug databases.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to kill cancer cells. The most common type of radiation therapy is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation given from a machine outside the body.

Radiation therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma is generally used only in emergency or life-threatening situations. For example, it may be used to treat pressure from a tumor on the windpipe or spinal cord. Also, it is used if the lymphoma affected the central nervous system at diagnosis or to prevent recurrence of lymphoma in the central nervous system.

Side effects from radiation therapy include fatigue, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements. Most side effects go away soon after treatment is finished.

Bone marrow transplantation

In a bone marrow transplant (BMT), the doctor first gives high doses of chemotherapy to destroy all of the child's bone marrow. The doctor then takes healthy marrow from a donor whose tissue matches the child's as closely as possible. The healthy marrow is infused into the child's vein. It finds its way to the bones and replaces the destroyed marrow.

The best match for bone marrow comes from the patient's brother or sister. But other people, including those who are not related to the child, may have a close enough match if a sibling's marrow is not available. When the bone marrow comes from a donor, it is called an allogeneic BMT.

In an autologous BMT, the child's own bone marrow is used. The bone marrow stem cells (cells that develop into many different types of cells) are removed from the child's peripheral blood or bone marrow, treated to destroy the cancer cells, and then frozen. The child then receives the treatment to eliminate his or her own bone marrow. The frozen marrow is thawed and injected to replace the destroyed marrow. The advantage of this method is that there is no risk of rejection, because the child receives his or her own marrow. One drawback is that if the treatment does not kill all of the cancer cells, the lymphoma could return to the child's body.

Recurrent non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Choice of treatment for recurrent non-Hodgkin lymphoma depends on three factors:

- Whether the tumor came back in the same place or in another part of the body

- The type of treatment the child had for the original tumor

- The overall health of the child

The doctor may use chemotherapy or BMT, or recommend a clinical trial.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and its treatments. For more detailed information on managing these and other side effects of cancer and cancer treatment, visit the PLWC Managing Side Effects section.

Diarrhea. Diarrhea is frequent, loose, or watery bowel movements. It is a common side effect of certain chemotherapeutic drugs or of radiation therapy to the pelvis, such as in women with uterine, cervical, or ovarian cancers. It can also be caused by certain tumors, such as pancreatic cancer.

Dry mouth (xerostomia). Xerostomia occurs when the salivary glands do not make enough saliva (spit) to keep the mouth moist. Because saliva is needed for chewing, swallowing, tasting, and talking, these activities may be more difficult with a dry mouth. Dry mouth can be caused by chemotherapy or radiation treatment, which can damage the salivary glands. Dry mouth caused by chemotherapy is usually temporary and normally clears up about two to eight weeks after treatment ends. Radiation treatment to the head, face, or neck can cause dry mouth and is most common with radiation treatment to the oral cavity to treat head and neck cancer. It can take six months or longer for the salivary glands to start producing saliva again after the end of treatment.

Fatigue (tiredness). Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness, and is the most common problem that people with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously impact family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even impact the will to live.

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin-sometimes unnoticeably-and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, the hair loss is usually temporary, and the hair often grows back.

Hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia is an unusually high level of calcium in the blood. Hypercalcemia can be life threatening and is the most common metabolic disorder associated with cancer, occurring in 10% to 20% of patients with cancer. While most of the calcium in the body is stored in the bones, about 1% of the body's calcium circulates in the bloodstream. Calcium is important for many bodily functions, including bone formation, muscle contractions, and nerve and brain function. Patients with hypercalcemia may experience loss of appetite, nausea and/or vomiting; constipation and abdominal pain; increased thirst and frequent urination; fatigue (tiredness), weakness, and muscle pain; changes in mental status, including confusion, disorientation, and difficulty thinking; and headaches. Severe hypercalcemia can be associated with kidney stones, irregular heartbeat or heart attack, and eventually loss of consciousness and coma.

Infection. An infection occurs when harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi (such as yeast) invade the body and the immune system is not able to destroy them quickly enough. Patients with cancer are more likely to develop infections because both cancer and cancer treatments (particularly chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the bones or extensive areas of the body) can weaken the immune system. Symptoms of infection include fever (temperature of 100.5°F or higher); chills or sweating; sore throat or sores in the mouth; abdominal pain; pain or burning when urinating or frequent urination; diarrhea or sores around the anus; cough or breathlessness; redness, swelling, or pain, particularly around a cut or wound; and unusual vaginal discharge or itching.

Mouth sores (mucositis). Mucositis is an inflammation of the inside of the mouth and throat, leading to painful ulcers and mouth sores. It occurs in up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy treatments. Mucositis can be caused by a chemotherapeutic drug directly, the reduced immunity brought on by chemotherapy, or radiation treatment to the head and neck area.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are common in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer and in some patients receiving radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS). SVCS is a collection of symptoms caused by the partial blockage or compression of the superior vena cava, the major vein that carries blood from the head, neck, upper chest, and arms to the heart. Nearly 95% of SVCS cases are caused by cancer. The most likely cancers to cause SVCS are lung cancer (especially small cell lung cancer), squamous cell lung cancer, adenocarcinoma of the lung, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, large cell lung cancer, and other cancers that spread to the chest. The superior vena cava, which drains into the right atrium of the heart, can become compressed when a tumor growing inside the chest presses on the vein. Because the superior vena cava lies close to a number of lymph nodes, any cancer that spreads to these lymph nodes, causing them to enlarge, can also cause SVCS. Enlarged lymph nodes compress the vein, which slows the blood flow and may ultimately result in complete blockage.

Thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia is an unusually low level of platelets in the blood. Platelets, also called thrombocytes, are the blood cells that stop bleeding by plugging damaged blood vessels and helping the blood to clot. Patients with low levels of platelets bleed more easily and are prone to bruising. Platelets and red and white blood cells are made in the bone marrow, a spongy, fatty tissue found on the inside of larger bones. Certain types of chemotherapeutic drugs can damage the bone marrow so that it does not make enough platelets. Thrombocytopenia caused by chemotherapy is usually temporary. Other medications used to treat cancer may also lower the number of platelets. In addition, a patient's body can make antibodies to the platelets, which lowers the number of platelets.

After Treatment

The treatment of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma often involves prolonged hospitalizations during each treatment cycle (one to two weeks). Also, some of the therapy may cause significant mucositis (inflammation of the mucous membranes) that may lead to pain, discomfort, and difficulty eating and drinking.

Most pediatric cancer programs provide psychologic support, financial guidance, and social services support to families. These services can reduce the emotional pain and financial discomfort and should be utilized to the fullest extent possible.

Long-term, follow-up care is critical for all children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Even though the risk of recurrence begins to decline after three years, there is still the potential of long-term complications of heart dysfunction and/or infertility. The risk of secondary cancers after treatment of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma is also possible, although the risks are only 1% to 2%. Yearly follow-up care by an experienced health-care team is highly encouraged for survivors of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma.