Overview

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a term that refers to many, very different types of lymphoma, a cancer of the lymph system. When lymphatic cells mutate (change) and grow unregulated by the processes that normally decide cell growth and death, they can form tumors.

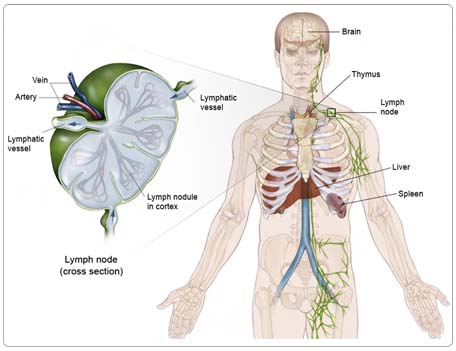

The lymph system is made up of thin tubes that branch out to all parts of the body. Its job is to fight infection and disease. The lymph system carries lymph, a colorless fluid containing white blood cells (called lymphocytes). Lymphocytes fight germs in the body. B-lymphocytes (also called B cells) make antibodies to fight bacteria, and T-lymphocytes (also called T cells) kill viruses and foreign cells and trigger the B cells to make antibodies.

Groups of bean-shaped organs called lymph nodes are located throughout the body at different sites in the lymph system. Lymph nodes are found in clusters in the abdomen, groin, pelvis, underarms, and neck. Other parts of the lymph system include the spleen, which makes lymphocytes and filters blood; the thymus, an organ under the breastbone; and the tonsils, located in the throat.

Because lymph tissue is found in so many parts of the body, NHL can start almost anywhere and can spread to almost any organ in the body. It most often begins in the lymph nodes, liver, or spleen, but can also involve the stomach, intestines, skin, thyroid gland, or any other part of the body.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing a disease, including cancer. There are risk factors that can be controlled, such as smoking, and risk factors that cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence disease, for many risk factors it is not known whether they cause the disease directly or they are simply a factor in causing the disease. Some people with several risk factors never develop the disease, while others with no known risk factors do. Knowing your risk factors and communicating with your doctor can help guide you in making wise lifestyle and health-care choices.

The exact cause of NHL is not known. The following factors can raise a person's risk of developing NHL:

Age. The risk of NHL increases with age. It occurs most commonly in people in their 60s and 70s.

Gender. Men are more likely to develop NHL than women.

Infections. Some types of NHL are associated with specific infections. For example, a type of lymphoma of the stomach, known as extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, also called MALT lymphoma, is thought to be caused by a bacterium known as Helicobacter pylori. If this lymphoma is diagnosed very early, the lymphoma will sometimes go away if the bacterium is eliminated from the stomach with antibiotics. Other types of MALT lymphoma, including those affecting the lungs and the tear glands, may also be caused by infections.

Virus exposure. Viruses are thought to be involved in causing some types of NHL. For example, EBV is associated with some types of NHL, including Burkitt's lymphoma, and lymphomas occurring after solid organ transplantations. However, the virus is probably not the only factor, so people who have had mono do not necessarily have an increased risk of developing NHL in the future. Other viruses have also been identified as being important in causing other rare types of lymphoma.

Immune deficiency disorders. Immune system disorders, such as HIV/AIDS, increase the risk of NHL.

Autoimmune disorders. People with autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjogren syndrome, are at an increased risk for developing certain types of NHL. Also, some drugs used to treat autoimmune disorders may increase the risk of NHL.

Organ transplantation. Organ transplantation recipients are at a higher risk for NHL because of the immune-suppressing drugs that must be taken.

Previous cancer treatment. Previous treatment with certain drugs for other cancers may increase the risk of NHL.

Chemical exposure. Exposure to certain chemicals, such as pesticides and petrochemicals, may increase the risk of NHL.

Symptoms

People with NHL often experience the following symptoms. Sometimes people with NHL do not show any of these symptoms. These symptoms may be similar to symptoms of other medical conditions. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your doctor.

The symptoms of NHL depend on where the cancer develops and the organ that is involved.

General symptoms:

- Swelling or lumps in the lymph nodes in the abdomen, groin, neck, or underarm

- Fever that cannot be explained by an infection or other illness

- Weight loss with no known cause

- Sweating and chills

Examples of symptoms related to tumor location:

- Tumors in the abdomen can cause a distended belly or pain.

- A tumor in the center of the chest pressing on the windpipe can cause difficulty breathing or other respiratory problems.

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has metastasized (spread). Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis. Imaging tests may be used to find out whether the cancer has metastasized. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

To determine if a person has NHL, the doctor will first take a complete medical history and do a physical examination, paying special attention to the lymph nodes, liver, and spleen. The doctor will also look for signs of infection that may cause the lymph nodes to swell and may prescribe antibiotics. If the swelling in the lymph nodes still does not go down, the swelling may be caused by something other than an infection. If the doctor still suspects lymphoma, he or she may also order a biopsy and laboratory and imaging tests.

The following tests may be used to diagnose NHL:

Biopsy. In a biopsy, the doctor cuts out a small piece of tissue and sends it to a pathologist, who examines it under a microscope for cancer cells. To diagnose lymphoma, the most common type of biopsy is a biopsy from lymph nodes in the neck, under the arms, or in the groin. Biopsies may also be taken from the chest or abdomen during a computerized tomography (CT) scan or from the stomach or intestine during an endoscopy. A biopsy is the only way to make a definite diagnosis of lymphoma and to determine the subtype.

Since many subtypes of lymphoma are identified by specific genetic changes or molecular activity, cytogenetics (the study of genetic changes in cells) and molecular studies may be performed on the biopsy sample. For example, the tumor cells of patients with mantle cell lymphoma contain a translocation of chromosomes 11 and 14, which means that parts of these two chromosomes have traded places. Other types of lymphoma are identified by abnormal amounts of other proteins.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. Lymphoma often spreads to the bone marrow, the spongy material in the center of bones where blood cells are produced. Sampling of the bone marrow can be important in the diagnosis of lymphoma and to determine if the cancer has spread.

The most common site to biopsy the bone marrow is the back of the pelvic (hip) bone. The skin is numbed and a needle is inserted into a bone in the hip until it reaches the marrow. A small amount of bone marrow is removed and examined under a microscope.

Computerized tomography (CT or CAT) scan. This is a special type of x-ray that uses a computer to capture a cross-sectional view of the inside of the body. A special dye is injected to help provide better detail and locate the exact position of a tumor. CT scans of the chest and abdomen can help find cancer that has spread to the lungs, lymph nodes, and liver.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This test uses powerful magnetic fields to view the inside of the body, including the brain and spinal column. MRIs create better images of certain tissues than CT scans and do not involve radiation.

Bone scans. Bone scans can show if cancer has spread to the skeletal system. In this procedure, the doctor injects a small amount of radioactive material into the vein. The substance collects in the bone, gives off gamma radiation, and can be detected by a special camera. Normal bone cells appear gray to the camera, and areas that have more cancer cells appear dark.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) scan. A PET scan is a test that creates an image of the body using an injection of a substance, such as glucose (sugar), in a low-dose, radioactive form to determine the metabolic activity in cells. It can show the difference between benign shadows and true malignancies that may show up on a CT scan or MRI. The exact accuracy and role of PET scanning in NHL is not yet clear, although high-grade aggressive lymphoma-containing masses often show up on PET scans. In the future, a PET scan may help determine the success of treatment for patients with aggressive types of lymphoma.

An FDG-PET scan is a procedure that involves injecting a patient with a radiolabeled glucose molecule known as FDG (18-fluorodeoxyglucose) that is more likely to be absorbed by the tumor cells. This special type of scan helps to evaluate where in the body there are tissues and masses that have high rates of metabolic activity.

Treatment

Through ongoing research, the medications used to treat cancer are constantly being evaluated in different combinations and to treat different cancers. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions.

The treatment of NHL depends on the stage of the cancer, whether the cancer has spread, and the person's overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan.

There are three main treatments for NHL: chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and biologic therapy. Since knowledge of genetic and chromosomal makeup of all cancers, including lymphoma, is developing rapidly, clinical trials of newer treatments may also be suitable for many patients.

Watchful waiting

Some patients with low-grade lymphoma may not require any treatment if they are otherwise well and the lymphoma is not causing any symptoms or problems with other organs. Patients are still closely monitored, but treatment only begins if symptoms or tests indicate that the cancer is progressing. Although this can be difficult to understand, there is very good evidence that, in some patients with low-grade lymphoma, the watch-and-wait approach does not adversely affect the chances of survival as long as regular and careful follow-up is performed.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of powerful drugs to kill cancer cells. It is the primary treatment for NHL. Chemotherapy may be given by mouth or injected into a vein.

The chemotherapeutic drugs used depend on the stage and type of the cancer. The most common chemotherapy regimen for lymphoma is called CHOP and contains four drugs: cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar), doxorubicin (Adriamycin), vincristine (Oncovin), and prednisone (a type of corticosteroid). Recent evidence has shown that for patients with B-cell lymphoma, the addition of a monoclonal antibody known as rituximab (Rituxan) (see monoclonal antibodies section below) to CHOP gives better results than the use of CHOP alone.

Chemotherapeutic drugs attack rapidly dividing cells, including those in normal tissues such as the hair, lining of the mouth, intestines, and bone marrow. Chemotherapy may cause people to lose their hair, develop mouth sores, or have nausea and vomiting. Chemotherapeutic drugs may lower the body's resistance to infection, cause fatigue, and lead to increased bruising and bleeding. Other side effects may include numbness and tingling in the fingers and toes, loss of appetite, constipation, or diarrhea. The severity of the side effects depends on the type of drug used, the dosage used, and how long it is taken.

Most side effects, including risk of infection, can be controlled during treatment and go away after chemotherapy is completed. Chemotherapy may also cause long-term side effects, also called late effects.

Radiation therapy

High energy x-rays are used to destroy cancer cells and shrink malignant tumors. Radiation for NHL is usually external-beam radiation therapy, which uses a machine to deliver x-rays to the site of the body where the cancer is located. For patients with lymphoma, it is mainly used with those who have early stage disease and is usually given following or in addition to chemotherapy. It is often given to patients who have mediastinal B-cell lymphoma.

Since radiation therapy kills healthy cells as well as cancer cells, patients may experience immediate side effects depending on the area of the body that is being irradiated. These may include mild skin irritations, upset stomach, loose bowel movements, nausea, and sore throat. Most patients feel tired. Many side effects can be helped by medication and usually go away when treatment is finished. Radiation therapy may also cause long-term side effects, also called late effects.

Biologic therapy

Also called immunotherapy, biologic therapy uses the body's immune system to fight cancer. Monoclonal antibodies, interferon, and vaccines are biologic therapies being tested in clinical trials as treatments for NHL.

Monoclonal antibodies. The monoclonal antibody, rituximab, is used to treat many different types of B-cell lymphoma. Rituximab works by targeting a cell-surface molecule called CD20. When the antibody attaches to this antigen, some lymphoma cells die and others appear to become more susceptible to chemotherapy. Although it is quite effective by itself, there is increasing evidence that, when added to chemotherapy for patients with most types of B-cell NHL, it produces better results than chemotherapy alone.

Radiolabeled antibodies. Radiolabeled antibodies are monoclonal antibodies with tethered radioactive particles that are designed to focus radioactivity directly to the lymphoma cells. This type of drug (ibritumomab tiuxetan [Zevalin] and tositumomab and iodine I 131 [Bexxar] are the two drugs currently available) is quite new and much is still being learned. In general, the radioactive antibodies are thought to be stronger than regular monoclonal antibodies but harder on the bone marrow.

Interferon. Interferons are proteins that help strengthen the immune system and are given alone or together with chemotherapy for some types of low-grade lymphoma.

Stem cell transplantation

This technique is a way of treating NHL with very high doses of chemotherapy to kill cancer cells and introducing new stem cells into the body that can form new blood cells. It is a difficult but relatively safe treatment and is reserved for patients with NHL whose disease is progressive or recurrent.

Stem cells are blood-forming cells that are usually found in the bone marrow. They can be collected and used for transplantation, either from the bone marrow space in the hipbone or, more commonly, from the blood.

First, stem cells from the bone marrow are "mobilized" into the blood by treating the patient with chemotherapy and another drug known as G-CSF (granulocyte colony stimulating factor). The stem cells are then collected from the blood, frozen, and stored. After this, the patient receives very high doses of chemotherapy (sometimes also with radiation therapy) to treat the NHL. These high doses are used since patients who undergo this treatment have disease that has proven to be resistant to normal chemotherapy doses. Higher doses of chemotherapy are more effective against recurrent NHL than standard doses of chemotherapy.

Although the patient's bone marrow may have been severely damaged by this high-dose chemotherapy treatment, the stem cells will be given back to the patient after the high-dose therapy and will restore blood cell production.

If the stem cells come from the patient, it is called an autologous transplantation. If the marrow comes from another person, it is called an allogeneic transplantation.

A mini-allogeneic transplantation is one that uses reduced intensity treatments before the transplantation. It is sometimes given to patients who may be too old or may not have the strength to go through the standard bone marrow transplantation process and is being evaluated in clinical trials to determine if it is effective in treating lymphoma.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to NHL and its treatments.

Diarrhea. Diarrhea is frequent, loose, or watery bowel movements. It is a common side effect of certain chemotherapeutic drugs or of radiation therapy to the pelvis, such as in women with uterine, cervical, or ovarian cancers. It can also be caused by certain tumors, such as pancreatic cancer.

Dry mouth (xerostomia). Xerostomia occurs when the salivary glands do not make enough saliva (spit) to keep the mouth moist. Because saliva is needed for chewing, swallowing, tasting, and talking, these activities may be more difficult with a dry mouth. Dry mouth can be caused by chemotherapy or radiation treatment, which can damage the salivary glands. Dry mouth caused by chemotherapy is usually temporary and normally clears up about two to eight weeks after treatment ends. Radiation treatment to the head, face, or neck can cause dry mouth and is most common with radiation treatment to the oral cavity to treat head and neck cancer. It can take six months or longer for the salivary glands to start producing saliva again after the end of treatment.

Fatigue (tiredness). Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness and is the most common problem patients with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously affect family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even affect the will to live.

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin—sometimes unnoticeably—and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, the hair loss is usually temporary, and the hair often grows back.

Hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia is an unusually high level of calcium in the blood. Hypercalcemia can be life threatening and is the most common metabolic disorder associated with cancer, occurring in 10% to 20% of patients with cancer. While most of the calcium in the body is stored in the bones, about 1% of the body's calcium circulates in the bloodstream. Calcium is important for many bodily functions, including bone formation, muscle contractions, and nerve and brain function. Patients with hypercalcemia may experience loss of appetite, nausea and/or vomiting; constipation and abdominal pain; increased thirst and frequent urination; fatigue, weakness, and muscle pain; changes in mental status, including confusion, disorientation, and difficulty thinking; and headaches. Severe hypercalcemia can be associated with kidney stones, irregular heartbeat or heart attack, and eventually loss of consciousness and coma.

Infection. An infection occurs when harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi (such as yeast) invade the body and the immune system is not able to destroy them quickly enough. Patients with cancer are more likely to develop infections because both cancer and cancer treatments (particularly chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the bones or extensive areas of the body) can weaken the immune system. Symptoms of infection include fever (temperature of 100.5°F or higher); chills or sweating; sore throat or sores in the mouth; abdominal pain; pain or burning when urinating or frequent urination; diarrhea or sores around the anus; cough or breathlessness; redness, swelling, or pain, particularly around a cut or wound; and unusual vaginal discharge or itching.

Mouth sores (mucositis). Mucositis is an inflammation of the inside of the mouth and throat, leading to painful ulcers and mouth sores. It occurs in up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy treatments. Mucositis can be caused by a chemotherapeutic drug directly, the reduced immunity brought on by chemotherapy, or radiation treatment to the head and neck area.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are common in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer and in some patients receiving radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS). SVCS is a collection of symptoms caused by the partial blockage or compression of the superior vena cava, the major vein that carries blood from the head, neck, upper chest, and arms to the heart. Nearly 95% of SVCS cases are caused by cancer. The most likely cancers to cause SVCS are lung cancer (especially small cell lung cancer), squamous cell lung cancer, adenocarcinoma of the lung, NHL, large cell lung cancer, and other cancers that spread to the chest. The superior vena cava, which drains into the right atrium of the heart, can become compressed when a tumor growing inside the chest presses on the vein. Because the superior vena cava lies close to a number of lymph nodes, any cancer that spreads to these lymph nodes, causing them to enlarge, can also cause SVCS. Enlarged lymph nodes compress the vein, which slows the blood flow and may ultimately result in complete blockage.

Thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia is an unusually low level of platelets in the blood. Platelets, also called thrombocytes, are the blood cells that stop bleeding by plugging damaged blood vessels and helping the blood to clot. Patients with low levels of platelets bleed more easily and are prone to bruising. Platelets and red and white blood cells are made in the bone marrow, a spongy, fatty tissue found on the inside of larger bones. Certain types of chemotherapeutic drugs can damage the bone marrow so that it does not make enough platelets. Thrombocytopenia caused by chemotherapy is usually temporary. Other medications used to treat cancer may also lower the number of platelets. In addition, a patient's body can make antibodies to the platelets, which lowers the number of platelets.

After Treatment and Late Effects of Treatment

After treatment is completed, patients should continue to see their doctor on a regular basis for physical examinations, blood tests, and possibly scans or other imaging studies. For the first two years, clinic visits are usually every two or three months. If there is still no evidence of disease, patients will not have to see the doctor as often, but should still return at least once a year for a checkup. Normally, follow-up visits are most frequent in the first three years after treatment. Follow-up visits usually continue for life.

Patients who have undergone treatment for lymphoma have an increased risk of developing other diseases or conditions later in life, as the toxicity of chemotherapy or radiation treatment can cause permanent damage. Treatments have already improved in the last 30 years, and now patients who have been through treatment for lymphoma are less likely to experience late effects, but there is still some risk. Therefore, it is important that patients stay current with their follow-up care to monitor any developments.

- Patients who have received radiation therapy to the pelvis and high doses of cyclophosphamide are at risk for sterility.

- All survivors of lymphoma are at higher risk for up to 20 years than the general population to develop a second cancer, most often of the lung, brain, kidney, bladder, or melanoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, or leukemia.

- Patients who receive doxorubicin-based chemotherapy or radiation treatment to the chest may be at higher risk for developing heart problems.

- Patients who receive bone marrow transplantation or peripheral blood stem cell support may be at higher risk for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

- Adults who receive certain types of chemotherapy (alkylating agents and methotrexate [MTX, Amethopterin]) or radiation treatment to the chest area may be at risk for lung damage and shortness of breath later in life.

- Patients who receive radiation treatment to the neck or chest are at increased risk for thyroid deficiency later in life, and women are at increased risk for breast cancer.

- Children who receive radiation treatment and chemotherapy to the brain and spinal cord area may be at risk for stunted growth, learning disabilities, and delayed puberty. Teenagers who receive chemotherapy may be at higher risk for low sperm counts or damage to the ovaries.

- Children who receive total body irradiation (TBI) as part of the bone marrow transplantation process may experience thyroid problems.

Advanced disease

If NHL recurs (comes back) after treatment is finished, it is called recurrent NHL (or relapsed or refractory disease). Choice of treatment for recurrent NHL depends on three factors: where the cancer comes back, the type of treatment given previously, and the patient's overall health. The doctor may use chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation or may recommend a clinical trial, a research study that evaluates new methods of treatment.