Overview

Hodgkin lymphoma, also called Hodgkin's disease, is one category of lymphoma, a cancer of the lymph system. When lymphatic cells mutate (change) and grow unregulated by the processes that normally decide cell growth and death, they can form tumors.

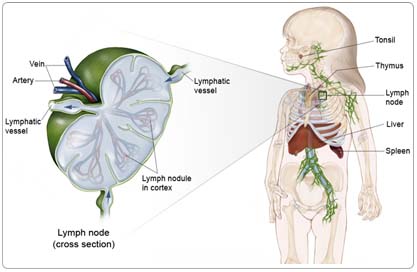

The lymph system is made up of thin tubes that branch out to all parts of the body. Its job is to fight infection and disease. The lymph system carries lymph, a colorless fluid containing white blood cells called lymphocytes. Lymphocytes fight germs in the body. B-lymphocytes (also called B-cells) make antibodies to fight bacteria, and T-lymphocytes (also called T-cells) kill viruses and foreign cells and trigger the B-cells to make antibodies.

Groups of bean-shaped organs called lymph nodes are located throughout the body at different sites in the lymph system. Lymph nodes are found in clusters in the abdomen, groin, pelvis, underarms, and neck. Other parts of the lymph system include the spleen, which makes lymphocytes and filters blood; the thymus, an organ under the breastbone; and the tonsils, located in the throat.

Hodgkin lymphoma most often starts in two places: the neck (cervical lymph nodes) and an area between the lungs, breastbone, and spine (mediastinal lymph nodes). Because there is lymph tissue in many parts of the body, Hodgkin lymphoma can start in any of the lymph nodes. If the cancer spreads outside the lymphatic system, Hodgkin lymphoma most often involves the lungs, bones, bone marrow, and liver.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing a disease, including cancer. There are risk factors that can be controlled, such as smoking, and risk factors that cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence disease, for many risk factors it is not known whether they actually cause the disease directly. Some people with several risk factors never develop the disease, while others with no known risk factors do.

The cause of Hodgkin lymphoma is unknown, and no definite link has been made with any virus or infection. Infection with the Epstein-Barr virus may be a trigger for developing the cancer in approximately 30% of children and teens. People with immune system problems also have a higher risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma. This group includes:

- Children born with ataxia telangiectasia (immune system problems)

- Children who are infected with the HIV/AIDS virus

- Children who are taking immune system lowering drugs following an organ transplantation

Symptoms

Children with Hodgkin lymphoma may experience the following symptoms. Sometimes, children with Hodgkin lymphoma do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be similar to symptoms of other medical conditions. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your child's doctor:

- Painless swelling of lymph nodes in the neck, underarm, or groin that doesn't go away in a few weeks

- Unexplained fever (without other signs of infection) that doesn't go away

- Itching

- Fatigue (tiredness)

- Unintended weight loss without dieting

- Night sweats (usually drenching)

If the lymph nodes in the chest are affected, they may press on the windpipe and cause coughing or problems breathing.

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has metastasized (spread). Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For Hodgkin lymphoma, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. Because Hodgkin lymphoma tends to spread from one lymph node group to the next adjacent group, imaging tests are used to find out the extent of spread of the disease and to see whether it has metastasized to regions other than the lymph nodes. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

The following tests may be used to diagnose Hodgkin lymphoma:

Physical examination. Children tend to have larger lymph nodes than adults. Usually a child will have enlarged lymph nodes for several weeks or months before a family doctor suspects Hodgkin lymphoma. The doctor will first look for signs of infection that may cause the lymph nodes to swell and may prescribe antibiotics.

If swelling in the lymph nodes doesn't go down after a course of antibiotics, the swelling may be caused by something other than an infection. The doctor will do a physical examination of all the lymph node areas, liver, and spleen, which may be enlarged in children with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Laboratory tests check blood counts and assess how the liver and kidneys are working. There is no specific blood test that indicates Hodgkin disease, but nonspecific changes in blood counts (such as unexplained anemia) are sometimes more common in children with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Biopsy. If the lymph nodes don't feel normal when the doctor examines them and don't respond to antibiotics, the doctor will check tissue from the abnormal lymph node for cancer cells. Hodgkin lymphoma produces a distinctive kind of abnormal cell that is easily identified under the microscope. The only way to make the diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma is to look at the tissue from an abnormal lymph node under the microscope. The process of removing the tissue is called a biopsy.

To perform a standard biopsy, a surgeon cuts through the skin and removes an entire lymph node or a piece of a mass of lymph nodes. If the lymph node mass is near the surface, the child may receive a local anesthetic, usually with sedation. If it is deeper inside the body, a general anesthetic will be used.

Sometimes, a doctor may first try to obtain tissue from the lymph node by doing a fine needle aspiration biopsy. In this test, a thin needle attached to a syringe is used to remove small amounts of fluid and tissue from the lymph node. This approach may not provide sufficient tissue to diagnose the disease, so it is recommended only when a standard biopsy is deemed too difficult or dangerous.

After a biopsy confirms the diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma, several tests and scans can show how far the disease has spread (a process called staging).

Chest x-ray. An x-ray is a picture of the inside of the body. A chest x-ray will show whether lymph nodes in the mediastinum (chest cavity) are enlarged. Mediastinal masses that take up one-third or more of the chest cavity are considered "bulky." They may cause coughing or breathing problems because of narrowing of the airway.

Computerized tomography (CT or CAT) scan. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the child's body with an x-ray machine. A computer then combines these images into a detailed, cross-sectional view that shows any abnormalities or tumors. Sometimes, a contrast medium (a special dye) is injected into a vein to provide better detail. The CT scan shows if lymph nodes in the chest or abdomen are enlarged, which may be a sign of cancer. Also, this test will show if the cancer has metastasized to organs, such as the lungs, liver, or spleen.

Bone scan. This test shows if Hodgkin lymphoma has spread to the bones. Bone metastases are not common in children with Hodgkin lymphoma, so this test is usually performed only in children who appear to have more advanced or widespread disease at diagnosis. These include children with bone pain or other signs of spread of Hodgkin lymphoma outside of the lymphatic system.

Gallium and positron-emission tomography (PET) scans. In a PET scan, radioactive sugar molecules are injected into the body. Cancer cells absorb sugar more quickly than normal cells, so they light up on the PET scan. PET scans are often used to complement information gathered from CT scan, MRI, and physical examination. These tests are used to evaluate a person's response to treatment. Before therapy, areas of active Hodgkin lymphoma appear black or "hot" on the scan in most people. During and after therapy, these "hot" areas usually go away as the cancer cells are dying. This test can reassure families and doctors, without doing a biopsy, that scar tissue still present on a CT scan after therapy does not contain active cancer cells.

Bone marrow biopsy. Hodgkin lymphoma rarely spreads to the bone marrow in children with localized Hodgkin lymphoma. Nonetheless, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended in most children because the presence of marrow disease would significantly affect the amount of therapy needed. Those with signs of more widespread disease involving lymph glands above and below the diaphragm, and those with other signs of Hodgkin lymphoma that has spread outside of the lymph node system to the lungs, liver, or bones are more likely to have disease present in the bone marrow.

Treatment

Through ongoing research, the medications used to treat cancer are constantly being evaluated in different combinations and to treat different cancers. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions.

Clinical trials are the standard of care for the treatment of children with cancer. In fact, more than 60% of children with cancer are treated as part of a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies that compare the standard treatments (best treatments available) with newer treatments that may be more effective. Cancer in children is rare, so it can be hard for doctors to plan treatments unless they know what has been most effective in other children. Investigating new treatments involves careful monitoring using scientific methods and all participants are followed closely to track progress.

To take advantage of these newer treatments, all children with cancer should be treated at a specialized cancer center. Doctors at these centers have extensive experience in treating children with cancer and have access to the latest research. Many times, a team of doctors treats children with cancer. Pediatric cancer centers often have extra support services for children and their families, such as nutritionists, social workers, and counselors. Special activities for kids with cancer may also be available. An increasing number of pediatric cancer centers also have services for teenagers and young adults. Sometimes, adult cancer centers participate in the same studies for these teens and young adults.

Treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma consists of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. There is no role for surgery as a treatment approach, except in some cases of localized lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin disease (LPHD). For children and adolescents, chemotherapy is always used with only rare exceptions (for example, some doctors may use radiation therapy only for high neck disease) because full-dose radiation (30-45 Gy) therapy has been associated with significant potential for hypoplasia (in growing children) and second malignant neoplasms (especially breast cancer) as well as thyroid, cardiac, gonadal, and pulmonary toxicity.

Classic treatments for Hodgkin lymphoma were ABVD (doxorubicin [Adriamycin], bleomycin [Blenoxane], vinblastine [Velban], dacarbazine [DTIC]) or MOPP (mechlorethamine[Mustargen], vincristine [Oncovin], prednisone, procarbazine [Matulane]). These regimens are no longer the standard of care for children because regimens with reduced long toxicities are available. Newer regimens for children use many of these agents, but replace nitrogen mustard with cyclophosphamide [Cytoxan, Neosar] and often replace procarbazine with etoposide [VePesid] to limit the risk of sterility. More recently, regimens for advanced stage disease have been designed to improve effectiveness by using more dose-density therapies (ABVE-PC, Stanford V, BEACOPP), often administered for shorter deviations.

Radiation therapy remains a primary therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatric approaches use lower dose (20-25 Gy) and reduced volume (involved field) compared with traditional regimens. The need for radiation therapy is determined by both stage of disease and response to chemotherapy. Clinical trials are currently in progress to identify the patients that are most likely to respond well enough to chemotherapy that they may not need radiation therapy.

The amount and type of therapy used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma depends on how many lymph node areas are involved and how large the nodes have grown. Children with more widespread (advanced) or "bulky" disease may have more rounds of chemotherapy and radiation therapy than children with early stage disease. New studies of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma are trying to further reduce the amount of treatment to avoid long-term side effects.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of x-rays or other particles to kill cancer cells. The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation therapy given from a machine outside the body. Older treatments for Hodgkin lymphoma used high doses of radiation therapy to all of the lymph node areas. Children treated this way had problems with the growth of muscles and bones and had a higher risk of second cancers as they got older.

Today, treatment with radiation therapy alone is rarely used in children. Doctors combine chemotherapy with low-dose radiation treatment given to areas where lymph nodes contain cancer.

Short-term side effects from radiation therapy include tiredness, sore throat, dry mouth, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements.

Long-term side effects of radiation therapy may include growth problems of bones and soft tissues; thyroid, heart, and lung problems; and second cancers. The risk of long-term side effects is much lower with newer radiation therapy techniques that deliver low doses only to cancerous lymph nodes while protecting normal tissues. Ongoing trials are attempting to define which patients need radiation therapy and how much radiation is needed. In general, those whose disease responds well to chemotherapy are receiving less radiation (or even no radiation) therapy. While the risk of breast cancer increases after high-dose radiation therapy in girls treated around the time of puberty, the risk of lower doses is less understood. Since early atherosclerotic heart disease, another significant, long-term risk of radiation therapy, affects boys as well, the current approach is to limit radiation therapy for both boys and girls, if possible. However, radiation therapy is a very effective therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma and plays a major role in achieving a cure.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Systemic chemotherapy uses drugs to target cancer cells throughout the body.

Because chemotherapy attacks rapidly dividing cells, including those in normal tissues such as the hair, lining of the mouth, intestines, and bone marrow, children receiving chemotherapy may lose their hair, develop mouth sores, or have nausea and vomiting. In addition, chemotherapy may lower the body's resistance to infection, lead to increased bruising and bleeding, and cause fatigue. These side effects can be controlled during treatment and usually go away after chemotherapy is completed. The severity of the side effects depends on the type and amount of the drug being given and the length of time the child receives the drug.

The long-term side effects of chemotherapy also depend on the type and total dose of each drug. Higher doses of chemotherapy can affect heart and lung function and cause infertility (the inability to have children) in the future. Rarely, children with Hodgkin lymphoma develop a second cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, because of chemotherapy's effects on bone marrow function. Fortunately, the risk of long-term side effects is much lower with newer treatment plans that limit the doses of drugs that cause serious health problems. The pediatric clinical trials now in use in most institutions use considerably less amounts of the drug that may affect the heart (doxorubicin) than the dosages used in many regimens for adults (particularly for advanced stage disease). The drugs being tested are also unlikely to cause sterility or infertility (procarbazine is no longer used in these trials). Current pediatric clinical trials also evaluate reduced doses of drugs that may cause leukemia.

Doctors may recommend treatment with chemotherapy alone or a combination regimen with chemotherapy and radiation therapy for children with Hodgkin lymphoma. Studies are ongoing to compare the benefits and risks of using radiation therapy for intermediate-risk patients who are rapid responders to chemotherapy. For later stage disease, current trials often include radiation therapy. For earlier stage disease, many study regimens do not include radiation therapy for those who respond well to chemotherapy.

For children with bulky and symptomatic disease, many doctors feel that the combination treatment gives the best chance for cure because there are two ways to attack the cancer cells. In combination treatment, doctors reduce the total amount of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which should reduce health problems after treatment. The most important consideration is to use sufficient therapy to cure the disease with the first treatment plan because the intensity of therapy for recurrent disease is high.

Recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma

Recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma is disease that comes back after treatment. Sometimes the disease comes back in the same area it began or in a new area of the body. Treatment for recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma depends on where the disease recurs, the type of therapy the child has had previously, and the time since the first therapy was completed. For example, if radiation therapy was the original treatment, then chemotherapy may be used as a second treatment. If chemotherapy was given initially, then the child may be given another round of chemotherapy using different drugs. Ifosfamide (Ifex) and vinorelbine (Navelbine) have recently been shown to be an effective treatment for recurrent disease in children and adolescents, and are now the standard drugs recommended prior to transplantation in the Children's Oncology Group studies. The combination of gemcitabine (Gemzar) with vinorelbine is being studied for its effectiveness in children.

If the disease has come back very soon after the first treatment or after the use of both chemotherapy and radiation therapy, more aggressive therapy including a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) may be recommended to increase the chances of keeping the disease in remission.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Often when high doses of chemotherapy or radiation therapy are used to treat recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma the bone marrow becomes damaged and can't produce healthy blood cells. To replace those lost cells, a hematopoietic SCT may be performed.

Peripheral blood stem cells are self-renewing cells found in the bone marrow. Stem cells create all other types of blood cells. The doctor harvests stem cells from the child's blood or bone marrow and freezes them to protect them from the high-dose chemotherapy the child will receive during treatment. After chemotherapy, the stem cells are thawed and returned to the body through transfusion. After four to six weeks, the stem cells start to produce new blood cells from the bone marrow.

In autologous hematopoietic SCT, stem cells are removed from a child's own bone marrow or blood and stored. The child then receives aggressive treatment with high doses of chemotherapy or radiation therapy (or both) to destroy the recurrent cancer cells. When this therapy is completed, the stored cells are then returned to the body. This stimulates the production of healthy blood cells and restores immune function.

In allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT), a person receives stem cells from a donor. The donor's tissue must be genetically matched, typically from a family member, for the transplantation to be successful. Allogeneic transplants have not been used as frequently in patients with recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma because of the greater risks of serious side effects. An ongoing study in the Children's Oncology Group is trying to achieve the benefits of allogeneic transplantation without the risks by using drugs (cyclosporine [Neoral], interferon gamma [Actimmune], and interleukin-2 [Proleukin]) that may cause the immune system to attack the tumor cells.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to Hodgkin lymphoma, and its treatments. For more detailed information on managing these and other side effects of cancer and cancer treatment, visit the PLWC Managing Side Effects section.

Diarrhea. Diarrhea is frequent, loose, or watery bowel movements. It is a common side effect of certain chemotherapeutic drugs or of radiation therapy to the pelvis, such as in women with uterine, cervical, or ovarian cancers. It can also be caused by certain tumors, such as pancreatic cancer.

Dry mouth (xerostomia). Xerostomia occurs when the salivary glands do not make enough saliva (spit) to keep the mouth moist. Because saliva is needed for chewing, swallowing, tasting, and talking, these activities may be more difficult with a dry mouth. Dry mouth can be caused by chemotherapy or radiation treatment, which can damage the salivary glands. Dry mouth caused by chemotherapy is usually temporary and normally clears up about two to eight weeks after treatment ends. Radiation treatment to the head, face, or neck can cause dry mouth and is most common with radiation treatment to the oral cavity to treat head and neck cancer. It can take six months or longer for the salivary glands to start producing saliva again after the end of treatment.

Fatigue (tiredness). Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness, and is the most common problem that people with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously impact family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even impact the will to live.

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin—sometimes unnoticeably—and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, the hair loss is usually temporary, and the hair often grows back.

Hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia is an unusually high level of calcium in the blood. Hypercalcemia can be life threatening and is the most common metabolic disorder associated with cancer, occurring in 10% to 20% of patients with cancer. While most of the calcium in the body is stored in the bones, about 1% of the body's calcium circulates in the bloodstream. Calcium is important for many bodily functions, including bone formation, muscle contractions, and nerve and brain function. Patients with hypercalcemia may experience loss of appetite, nausea and/or vomiting; constipation and abdominal pain; increased thirst and frequent urination; fatigue (tiredness), weakness, and muscle pain; changes in mental status, including confusion, disorientation, and difficulty thinking; and headaches. Severe hypercalcemia can be associated with kidney stones, irregular heartbeat or heart attack, and eventually loss of consciousness and coma.

Infection. An infection occurs when harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi (such as yeast) invade the body and the immune system is not able to destroy them quickly enough. Patients with cancer are more likely to develop infections because both cancer and cancer treatments (particularly chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the bones or extensive areas of the body) can weaken the immune system. Symptoms of infection include fever (temperature of 100.5°F or higher); chills or sweating; sore throat or sores in the mouth; abdominal pain; pain or burning when urinating or frequent urination; diarrhea or sores around the anus; cough or breathlessness; redness, swelling, or pain, particularly around a cut or wound; and unusual vaginal discharge or itching.

Mouth sores (mucositis). Mucositis is an inflammation of the inside of the mouth and throat, leading to painful ulcers and mouth sores. It occurs in up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy treatments. Mucositis can be caused by a chemotherapeutic drug directly, the reduced immunity brought on by chemotherapy, or radiation treatment to the head and neck area.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are common in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer and in some patients receiving radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia is an unusually low level of platelets in the blood. Platelets, also called thrombocytes, are the blood cells that stop bleeding by plugging damaged blood vessels and helping the blood to clot. Patients with low levels of platelets bleed more easily and are prone to bruising. Platelets and red and white blood cells are made in the bone marrow, a spongy, fatty tissue found on the inside of larger bones. Certain types of chemotherapeutic drugs can damage the bone marrow so that it does not make enough platelets. Thrombocytopenia caused by chemotherapy is usually temporary. Other medications used to treat cancer may also lower the number of platelets. In addition, a patient's body can make antibodies to the platelets, which lowers the number of platelets.

After Treatment

People with Hodgkin lymphoma are most often adolescents or young adults. While the treatment period is limited (usually less than months) and the outcome is excellent (overall survival is greater than 85%), there are long-term consequences as a result of therapy. These include cardiac (after doxorubicin, radiation therapy), pulmonary (bleomycin, radiation therapy), thyroid (radiation therapy), secondary cancer (radiation therapy or chemotherapy), and reproductive effects (procarbazine, nitrogen mustard, pelvic radiation). Those who had a splenectomy (surgical removal of the spleen) have an ongoing risk of serious infection.

In most Hodgkin lymphoma survivors, the medical consequences do not significantly limit life span. However, Hodgkin lymphoma survivors report significant concerns regarding their health status compared with other survivors of childhood cancer. This may result from the psychosocial effects of treatment during adolescence, when the adolescent may feel "different" from healthy peers. In addition, many Hodgkin lymphoma survivors experience long-term fatigue that may require interventions, such as taking a reduced course load at college or choosing employment that is consistent with the individual's stamina. Sterility or infertility may also affect the young adult who is hoping to some day start a family. Newer reproductive technologies may help some of these individuals. Current regimens attempt to reduce exposure to alkylating agents to limit such risks.

Ongoing follow-up care by health-care professionals experienced in long-term consequences is important. Efforts at preventive health care include breast cancer screening (after mediastinal radiation therapy), smoking cessation (after bleomycin or radiation therapy due to enhanced lung cancer risk) and reduction of risk for atherosclerotic heart disease through exercise, diet, and medication. Providing the survivor of Hodgkin lymphoma with preventative measures that may foster better, long-term outcomes may be helpful by offering a degree of control of his or her own health status.