Overview

Lung cancer affects more than 200,000 Americans each year. Although cigarette smoking is the main cause, anyone can develop lung cancer. Lung cancer is always treatable, no matter the size, location, or if the cancer has spread.

The lungs absorb oxygen from the air and bring the oxygen into the bloodstream for delivery to the rest of the body. As the body's cells use oxygen, they release carbon dioxide. The bloodstream carries carbon dioxide back to the lungs, and the carbon dioxide leaves the body when people exhale. The lungs contain many different types of cells. Most cells in the lung are epithelial cells. Epithelial cells line the airways and produce mucus, which lubricates and protects the lung. The lung also contains nerve cells, hormone-producing cells, blood cells, and structural or supporting cells.

There are two major types of lung cancer: Non-small cell, and Small cell. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) arises from epithelial cells and is the most common type. Small cell lung cancer begins in the nerve cells or hormone-producing cells. The term "small cell" refers to the size and shape of the cancer cells as seen under a microscope. It is important for doctors to distinguish Non-small cell from Small cell lung cancer because the two types of cancer are usually treated in different ways.

Lung cancer begins when cells in the lung grow out of control and form a lump (also called a tumor, mass, lesion, or nodule). A cancerous tumor is a collection of a large number of cancer cells and appears as a lump within the lung tissues. A lung tumor can begin anywhere in the lung.

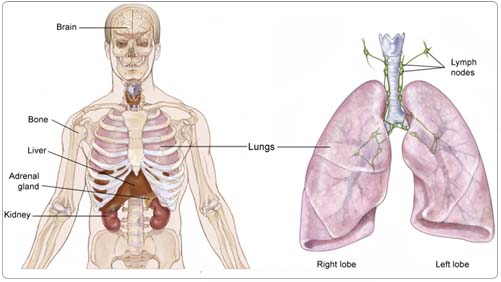

Once a cancerous lung tumor begins to grow, it may or may not shed cancer cells. Shed cells can be carried away in blood, or float away in the natural fluid, called lymph, that surrounds lung tissue. Lymph flows through tubes called lymphatic vessels, which drain into collecting stations called lymph nodes located in the lungs, in the center of the chest, and elsewhere in the body. The natural flow of lymph out of the lungs is toward the center of the chest, which explains why lung cancer often spreads there. When a cancer cell leaves its site of origin, and moves into a lymph node or to a far away part of the body through the bloodstream, it is called metastasis.

The location and size of the initial lung tumor, and whether it has spread to lymph nodes or more distant sites, determines the stage of lung cancer. The type of lung cancer (Non-small cell versus Small cell) and stage of the disease (discussed later in Staging) determine what type of treatment is needed.

Risk Factors and Prevention

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing cancer. Some risk factors can be controlled, such as smoking, and some cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence the development of cancer, most do not directly cause cancer. Some people with several risk factors never develop cancer, while others with no known risk factors do. However, knowing your risk factors and communicating them to your doctor may help you make more informed lifestyle and health-care choices.

The following factors can raise a person's risk of developing lung cancer:

Tobacco. Most lung cancer occurs in people who smoke. Tobacco smoke damages cells in the lungs, causing the cells to grow abnormally. The risk that smoking will lead to cancer is higher for people who smoke heavily and/or for a long time. Regular exposure to smoke from someone else's cigarettes, cigars, or pipes (called environmental or "secondhand" tobacco smoke) can increase a person's risk of lung cancer even if that person does not smoke.

Asbestos. These are hair-like crystals found in many types of rock and are often used as fireproof insulation in buildings. When asbestos fibers are inhaled, they can irritate the lung. Many studies show that the combination of smoking and asbestos exposure is particularly hazardous. People who work with asbestos in jobs (such as shipbuilding, asbestos mining, insulation, or automotive brake repair) and smoke have a higher risk of developing lung cancer. Using protective breathing equipment reduces this risk.

Radon. This is an invisible, odorless gas naturally released by some soil and rocks. Exposure to radon has been associated with an increased risk of some cancers, including lung cancer. Most hardware stores have kits that test home radon levels, and basements can be ventilated to reduce radon exposure.

The most important way to prevent lung cancer is to avoid tobacco smoke. People who never smoke have the lowest risk of lung cancer. People who smoke can reduce their risk of lung cancer by stopping smoking, but their risk of lung cancer will still be higher than people who never smoked. Attempts to prevent lung cancer with vitamins or other treatments have not worked. Beta-carotene, a drug related to vitamin A, has been tested for the prevention of lung cancer. It did not reduce the risk of cancer. In people who continued to smoke, beta-carotene actually increased the risk of lung cancer.

Screening

There are no tests recommended for screening the general population for lung cancer. Doctors still need to prove that screening everyone at risk for lung cancer reduces rates of death from lung cancer in the general population. A new test, called a low-dose helical (or spiral) computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan, is currently being studied for this purpose. Any person who is at increased risk because of smoking or asbestos exposure and is interested in being screened for lung cancer should consult their doctor to see if he or she should have a low-dose helical CT scan.

Symptoms

People with lung cancer may experience the following symptoms. Sometimes people with lung cancer do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be caused by a medical condition that is not cancer. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your doctor.

For people with lung cancer who have no symptoms, their lung cancer can be discovered on a chest x-ray or CT scan performed for some other reason, such as checking for heart disease. Most people with lung cancer are diagnosed when the tumor grows, takes up space, or begins to interfere with nearby structures. Lung tumors may also make fluid that can collect in the lung or the space around the lung. A tumor can push the air out of the lungs and cause the lung to collapse. In this way, lung tumors can prevent the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide by blocking the flow of air into the lungs, or by using up the space normally required for oxygen to come in and carbon dioxide to go out of the lung.

Symptoms of a lung cancer may include:

- Fatigue (tiredness)

- Cough

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain, if a tumor invades a structure within the chest or involves the lining of the lung

- Loss of appetite

- Coughing up phlegm or mucus

- Hemoptysis (coughing up blood)

Although lung cancer can metastasize (spread) anywhere in the body, the most common sites of spread are the lymph nodes, lungs, bones, brain, liver, and structures near the kidneys called the adrenal glands. Metastases (spread to more than one area) from lung cancer can cause further breathing difficulties, bone pain, abdominal or back pain, headache, weakness, seizures, and/or speech difficulties. Rarely, lung tumors can release hormones that result in chemical imbalances, such as low blood sodium levels or high blood calcium.

Symptoms such as fatigue, malaise (feeling out-of-sorts or unwell), and loss of appetite are not necessarily due to metastases. The presence of cancer anywhere in the body can cause a person to feel unwell in a general way. Loss of appetite can result in weight loss. Fatigue and weakness can further worsen breathing difficulties.

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has spread from the lung. Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. If a biopsy is not possible or more information is needed, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis. Imaging tests may be used to find out whether the cancer has metastasized, but they can never be used to actually diagnose lung cancer. Only a biopsy can do that. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Location of the suspected cancer

- Size of the suspected cancer

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

In addition to a physical examination, the following tests may be used to diagnose lung cancer:

Biopsy. A biopsy is the only way to make a diagnosis of lung cancer. A biopsy is the removal of a small amount of tissue for examination under a microscope. The sample removed from the biopsy is analyzed by a pathologist (a doctor who specializes in interpreting laboratory tests and evaluating cells, tissues, and organs to diagnose disease). If cancer cells are present, the pathologist will determine if it is Small cell lung cancer or NSCLC, based on its appearance under the microscope.

Common procedures doctors use to obtain tissue for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer are listed below:

Sputum cytology. If there is reason to suspect lung cancer, the doctor may ask a person to cough up some phlegm so it can be examined under the microscope. A pathologist can find cancer cells mixed in with the mucus.

Bronchoscopy. In this procedure, the doctor passes a thin, flexible tube with a light on the end into the mouth or nose, down through the main windpipe, and into the breathing passages of the lungs. A surgeon or a pulmonologist, a medical doctor who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of lung disease, may perform this procedure. The tube lets the doctor see inside the lungs. Tiny tools inside the tube can take samples of fluid or tissue, so the pathologist can examine them. Patients are given mild anesthesia (medication to put them to sleep) during a bronchoscopy.

Needle aspiration. After numbing the skin, a special type of radiologist, called an interventional radiologist, inserts a small needle through the chest and directly into the lung tumor. The doctor uses the needle to aspirate (suck out) a small sample of tissue for testing. Often, the radiologist uses a chest CT scan or special x-ray machine called a fluoroscope to guide the needle.

Bone marrow biopsy. For patients with Small cell lung cancer, doctors sometimes use a local anesthetic (to numb the area) and a special needle in order to remove a tiny piece of bone (typically from the hip bone) in order to determine whether small cell cancer is present within the bones.

Thoracentesis. After numbing the area, a needle is inserted through the chest wall and into the space between the lung and the wall of the chest where fluid can collect. The fluid is taken out and checked for cancer cells by the pathologist.

Thoracotomy. This procedure is performed in an operating room with the help of general anesthesia, which allows the person to "sleep" during this procedure. A surgeon then makes an incision in the chest, examines the lung directly, and takes tissue samples for testing. A thoracotomy is the procedure surgeons most often perform to completely remove a lung tumor.

Thoracoscopy. Through a small cut in the skin of the chest wall, a surgeon can insert a special instruments and a small video camera to assist in the examination of the inside of the chest. Patients require general anesthesia, but recovery time may be shorter given the smaller incisions. This procedure may be referred to as "VATS" (video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery).

Mediastinoscopy. A surgeon examines and takes a sample of the lymph glands in the center of the chest (underneath the breastbone) by making a small incision at the top of the breastbone. This procedure also requires general anesthesia and is done in an operating room.

Imaging tests

In addition to biopsies and surgical procedures, imaging scans are vital to the care of people with lung cancer. No test is perfect, and no scan can diagnose lung cancer. Only a biopsy can do that. Chest x-ray and scan results must be combined with a person's medical history, a physical examination, blood tests, and biopsy information to form a complete story about where the cancer began, and whether or where it has spread.

CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These scans produce images that allow doctors to see the size and location of lung tumors and/or lung cancer metastases. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body with an x-ray machine. A computer then combines these images into a detailed, cross-sectional view that shows any abnormalities or tumors. An MRI uses magnetic fields, not x-rays, to produce detailed images of the body. MRI scanning is imprecise when used to image a structure that is moving, like your lungs. For that reason, the MRI scan is rarely used to study the lungs themselves.

Scans are also available that use radioactive molecules, called tracers, injected into the blood to show where cancer is possibly located:

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan. In a PET scan, radioactive sugar molecules are injected into the body. Lung cancer cells absorb sugar more quickly than normal cells, so they light up on the PET scan. PET scans are often used to complement information gathered from CT scan, MRI, and physical examination. Normal tissues, such as the heart and brain, and benign tumors can also take up sugar quickly, like cancer. Specialists in nuclear medicine help your doctor interpret PET scans. There are some cancerous lung tumors do not take up sugar faster than normal tissues.

Bone scan. A bone scan uses a radioactive tracer to look at the inside of the bones. The tracer is injected into a patient's vein. It collects in areas of the bone and is detected by a special camera. Healthy bone appears gray to the camera, and areas of injury, such as those caused by cancer, appear dark.

Treatment

The treatment of lung cancer depends on the size and location of the tumor, whether the cancer has spread, and the person's overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan.

There are three basic ways to treat lung cancer: surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.

Surgery

A thoracic surgeon is specially trained to perform lung cancer surgery. The goal of surgery is complete removal of the lung tumor and the nearby lymph nodes in the chest. The tumor must be removed with a surrounding border of normal lung tissue (called the margin). A "negative margin" means that when the pathologist examines the lung, or piece of lung that has been removed by the surgeon, no traces of cancer were found in the healthy tissue surrounding the tumor.

The lungs have five lobes, three in the right lung and two in the left lung. For NSCLC, a lobectomy (removing of an entire lobe of the lung) has been shown to be the most effective type of surgery, even when the lung tumor is very small. If, for whatever reason, the surgeon cannot remove an entire lobe of the lung, the surgeon can remove the tumor in a procedure called a wedge, surrounded by a margin of normal lung. If the tumor is close to the center of the chest, the surgeon may have to perform a pneumonectomy (surgery to remove the entire lung). The time it takes to recover from lung surgery depends on how much of the lung is removed and the health of the patient before surgery.

Adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant therapy is treatment that is given after surgery to lower the risk of the lung cancer returning. Adjuvant therapies include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies. They are intended to eliminate any lung cancer cells that may be lingering in the body. Adjuvant therapy may decrease the risk of recurrence, but does not necessarily eliminate it.

Along with staging, other sophisticated tools can help determine prognosis and help you and your doctor make decisions about whether adjuvant therapy would be helpful in your treatment. The website Adjuvant! (www.adjuvantonline.com) is one such tool that your doctor can access to interpret a variety of factors that are important for making the treatment decision. This website should only be used in consultation with your doctor who best knows you and your medical condition.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy, or radiotherapy, refers to carefully aimed doses of radiation (high energy x-rays) intended to kill cancer cells. If you need radiation therapy, you will be asked to see a specialist called a radiation oncologist. Like surgery, radiation therapy cannot be used to treat widespread cancer. Radiation only kills cancer cells directly in the path of the radiation beam. It also damages the normal cells caught in its path, and for this reason, it cannot be used to treat large areas of the body. Patients with lung cancer treated with radiation therapy often experience fatigue and loss of appetite. If radiation therapy is given to the neck, or center of the chest, patients may also develop a sore throat and have difficulty swallowing. Skin irritation, like sunburn, may occur at the treatment site. Most of the side effects of radiation therapy go away after the treatment ends.

If the radiation therapy irritates or inflames the lung, patients may develop a cough, fever, or shortness of breath months and sometimes years after the radiation therapy ends. This condition occurs in about 15% of patients and is called radiation pneumonitis. If it is mild, radiation pneumonitis does not require treatment and resolves on its own. If it is severe, radiation pneumonitis may require treatment with steroid medications, such as prednisone. Radiation therapy may also cause permanent scarring of the lung tissue near the site of the original tumor. Typically, the scarring does not lead to symptoms. Widespread scarring can lead to permanent cough and shortness of breath. For this reason, radiation oncologists carefully plan the treatments using CT scans of the chest to minimize the amount of normal lung tissue exposed to the radiation beam.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy refers to the use of drugs to kill cancer cells throughout the body. Chemotherapy is given by a medical oncologist. Most chemotherapy used for lung cancer is injected into a vein (called intravenous, or IV injection). Although these drugs kill cancer cells, they may also cause side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. Nausea and vomiting are often avoidable; read the ASCO Patient Guide: Preventing Nausea and Vomiting Caused by Cancer Treatment for more information.

Chemotherapy may also damage normal cells in the body, including blood cells, skin cells, and nerve cells. This may result in low blood counts, an increased risk of infection, hair loss, mouth sores, and/or numbness or tingling in the hands and feet. Your medical oncologist can often prescribe drugs to help provide relief from many side effects. Hormone injections are also used to prevent white and red blood cell counts from becoming too low.

Newer chemotherapy treatment plans cause fewer side effects and are as effective as older treatments. Chemotherapy has been shown to improve both the length and quality of life in people with lung cancer of all stages.

Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications. Learn more about your prescriptions through PLWC's Drug Information Resources, which provides links to searchable drug databases.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy fights lung cancer by stopping the action of abnormal proteins that cause cancer cells to grow uncontrollably. These abnormal proteins are present in unusually large amounts in certain lung cancer cells. Two types of drugs target abnormal cells.

Monoclonal antibodies interfere with how the abnormal proteins actually enter the normal cell; they stop the entrance on the cell surface, which is like the doorway of the cell. Bevacizumab (Avastin) is a monoclonal antibody given in combination with chemotherapy. Drugs like bevacizumab block the formation of new blood vessels (also called angiogenesis), which is necessary for tumors to grow and spread. A clinical trial in 2005 showed that the one-year survival rate of patients with advanced lung cancer could be improved by 50% with the addition of bevacizumab to standard chemotherapy. The risk of serious bleeding for patients taking bevacizumab was raised to about 2%.

Erlotinib (Tarceva) is a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for locally advanced and metastatic NSCLC. It blocks the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a protein that helps lung cancer cells grow and multiply. This medication is a pill that can be taken by mouth. The side effects of erlotinib include rash that looks like acne and diarrhea.

Gefitinb (Iressa) is another drug that works like erlotinib. It is available only to people who were already taking it, had taken it in the past and had a good effect, or as part of a clinical trial.

Combining treatments

Most patients with lung cancer are treated by more than one specialist with more than one type of treatment. For example, chemotherapy can be prescribed before or after surgery, or before, during, or after radiation therapy. Patients should have a sense that their doctors have a coordinated plan of care and are communicating effectively with one another. If patients do not feel that the surgeon, radiation oncologist, or medical oncologist is communicating effectively with them or each other about the goals of treatment and the plan of care, patients should discuss this with their doctors or seek additional opinions before treatment.

Treatment of NSCLC

Stage I and II. In general, stage I and II NSCLC are treated with surgery. Surgeons cure many patients with an operation. Before or after surgery, a patient may be referred to a medical oncologist. Some patients with large tumors or evidence of spread to lymph nodes may benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy (chemotherapy before the surgery, also called induction chemotherapy) or adjuvant chemotherapy to reduce the chance the cancer will return. Radiation therapy is recommended to treat and cure lung tumors in people for whom surgery is not advisable.

Stage III. Stage III NSCLC has spread to the point that surgery or radiation therapy alone is not enough to cure the disease for most people. Patients with stage III disease have a high risk of the cancer returning, either in the same place or at a distant location, even after successful surgery or radiation therapy. For this reason, doctors generally do not recommend immediate surgery, and sometimes suggest chemotherapy with surgery to follow.

After chemotherapy, patients with stage IIIA NSCLC may still undergo surgery, especially if the chemotherapy is effective in killing or shrinking the cancer. Because chemotherapy travels throughout the body, if it is killing the cancer the doctors can see, it may also be killing the invisible cancer cells that may have escaped the original tumor. Following effective chemotherapy, surgeons can be more confident that removing a stage IIIA NSCLC will result in a cure.

Some patients with stage IIIA NSCLC are not treated with surgery. Instead, patients with stage IIIA disease may be treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy with the intent to cure. The chemotherapy may be delivered either before or at the same time as the radiation therapy. This method has shown to improve the ability of radiation therapy to shrink the cancer and to decrease the risk of the cancer returning. Chemotherapy delivered at the same time as radiation therapy is more effective than chemotherapy delivered before radiation therapy, but it results in more side effects. Patients who have received both chemotherapy and radiation therapy for stage IIIA disease may still go on to have surgery. However, there is debate among doctors whether surgery is necessary for patients effectively treated with radiation therapy and if radiation therapy is needed in patients whose tumors are completely removed following treatment with chemotherapy.

For the majority of patients with NSCLC, their tumors are unresectable (cannot be removed by surgery). This may be because they have stage IIIB lung cancer, or the surgeon feels that an operation would be too risky, or that the tumor cannot be removed completely. For patients with unresectable NSCLC, with no signs of spread of cancer to distant sites or in fluid around the lung, a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy can still be used to try to cure the patient.

Stage IIIB with pleural effusion and Stage IV NSCLC. Patients with stage IV NSCLC or stage IIIB due to malignant pleural effusion (cancer cells in the fluid around the lung) are typically not treated with surgery or radiation therapy. Rarely, doctors recommend that a brain or adrenal metastasis be removed surgically if that is the only place the cancer has spread. Radiation therapy can also be used to treat a single site of metastasis. However, patients with stage IV disease, or stage IIIB with a pleural effusion, are at very high risk for the cancer growing in a different location. Most patients with these stages of NSCLC are only treated with drugs.

The goals of chemotherapy are to shrink the cancer, relieve discomfort caused by the cancer, prevent further spread, and lengthen life. Rarely, chemotherapy can make metastatic lung cancer disappear. However, doctors know from experience that the cancer will return. Therefore, patients with stage IV disease, or stage IIIB with a pleural effusion, are never considered "cured" of their cancer no matter how well the chemotherapy works. These patients must be followed closely by their doctors and require lifelong chemotherapy to control their disease. Chemotherapy has been proven to improve both length and quality of life for patients with NSCLC.

For more information about NSCLC treatment that cannot be removed by surgery, read the ASCO Patient Guide: Advanced Lung Cancer.

Treatment of Small cell lung cancer

Small cell lung cancer spreads quickly and cannot be cured by surgery or radiation therapy alone. Patients with limited stage small cell lung cancer are best treated with simultaneous chemotherapy plus radiation therapy given twice a day. Radiation therapy is best when given during the first or second month of chemotherapy, with chemotherapy continuing for three to six months.

Patients with extensive stage disease are treated with chemotherapy only. In patients whose tumors have disappeared after chemotherapy, radiation therapy may help prevent cancer from later spreading to the brain. This preventative radiation to the head is called prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI). Like patients with advanced NSCLC, patients with Small cell lung cancer of any stage face the risk that their cancer can return, even when it is initially controlled. All patients with small cell lung cancer must be followed closely by their doctors with x-rays, scans, and check-ups.

To learn about the terms used in this section, read the PLWC Feature: Cancer Terms to Know: During Treatment

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has a series of treatment guidelines designed for patients and their loved ones. These guidelines offer people living with cancer and their families information to help them make timely and well-informed decisions. The NCCN treatment guide for lung cancer can be found at: http://www.nccn.org/patients/patient_gls/_english/_lung/contents.asp

Stopping smoking

Even after lung cancer is diagnosed, it is still not too late to benefit from stopping cigarette smoking. People who stop smoking have an easier time with all treatments, feel better, live longer, and have a lower risk of developing a second lung cancer. Stopping smoking is never easy and even harder when facing the diagnosis of lung cancer and treatment. People who smoke should seek help from family, friends, smoking cessation programs, and health care professionals. None of the smoking cessation aids available interfere with cancer treatment.

Controlling physical symptoms caused by lung cancer

Chemotherapy is not as effective as radiation or surgery to treat lung cancer that has spread to the brain. For this reason, lung cancer that has spread to the brain is treated instead with radiation therapy, surgery, or both. Most patients with brain metastases from lung cancer are treated with radiation therapy to the entire brain. This can cause side effects such as hair loss, fatigue, and redness of the scalp. With small tumors, a type of radiation therapy called stereotactic radiosurgery can focus radiation only on the tumor in the brain and minimize side effects.

Radiation therapy or surgery may also be used to treat metastases that are causing pain or other symptoms.

- Tumors in the chest that are bleeding or blocking the lung passages can be shrunk by radiation therapy.

- During a bronchoscopy (See Diagnosis), lung passages blocked by cancer can be opened to improve breathing.

- Surgeons can use lasers to burn away tumor or place mechanical stents (supports) to prop airway passages open.

- Bone metastases that weaken important bones can be treated with surgery and reinforced using metal implants. Bone metastases can also be treated with radiation therapy.

Medications can also help treat the symptoms of lung cancer.

- Medications are used to treat cancer pain. Most hospitals and cancer centers have pain control specialists on staff that design pain-relief treatments even for very severe cancer pain. Many drugs used to treat cancer pain, especially morphine, can also relieve shortness of breath caused by cancer.

- Medications can be used to suppress cough, open closed airways, or reduce bronchial secretions.

- Prednisone or methylprednisolone can reduce inflammation caused by lung cancer or radiation and improve breathing.

- Extra oxygen from small, portable tanks can help make up for the lung's reduced ability to extract oxygen from the air.

- Medications called bisphosphonates strengthen bones, lessen bone pain, and can help prevent future bone metastases.

- Appetite stimulants and nutritional supplements can improve appetite and lessen weight loss

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to lung cancer and its treatments. For more detailed information on managing these and other side effects of cancer and cancer treatment, visit the PLWC Managing Side Effects section.

Fatigue (tiredness). Fatigue is the feeling of exhaustion or tiredness, and is the most common problem that people with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously affect family and daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even affect the will to live.

Appetite loss. Appetite changes are common with cancer and cancer treatment, including chemotherapy. Individuals with a poor appetite or appetite loss may eat less than usual, not feel hungry at all, or feel satiated (full) after eating only a small amount. Ongoing appetite loss can lead to weight loss, malnutrition, and loss of muscle mass and strength. The combination of weight loss and loss of muscle mass, also called wasting, is referred to as cachexia.

Fluid around the lungs (pleural effusion). A pleural effusion is a condition characterized by extra fluid building up in the pleural space, the space between the edge of the lungs and the chest wall. A malignant pleural effusion is caused by cancer that grows in the pleural space. About half of patients with cancer develop a pleural effusion. More than 75% of patients with a malignant pleural effusion have lymphoma or cancers of the breast, lung, or ovary. The symptoms of a pleural effusion include dyspnea (shortness of breath), dry cough, pain, feeling of chest heaviness, inability to exercise, and malaise (feeling unwell).

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin-sometimes unnoticeably-and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, hair loss is usually temporary, and often grows back.

Infection. An infection occurs when harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi (such as yeast) invade the body and the immune system is not able to destroy them quickly enough. Patients with cancer are more likely to develop infections because both cancer and cancer treatments (particularly chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the bones or extensive areas of the body) can weaken the immune system. Symptoms of infection include fever (temperature of 100.5°F or higher); chills or sweating; sore throat or sores in the mouth; abdominal pain; pain or burning when urinating or frequent urination; diarrhea or sores around the anus; cough or breathlessness; redness, swelling, or pain, particularly around a cut or wound; and unusual vaginal discharge or itching.

Anemia. Anemia is common in people with cancer, especially those receiving chemotherapy. Anemia is an abnormally low level of red blood cells (RBCs). RBCs contain hemoglobin (an iron protein) that carries oxygen to all parts of the body. If the level of RBCs is too low, parts of the body do not get enough oxygen and cannot work properly. Most people with anemia feel tired or weak. The fatigue (tiredness) associated with anemia can seriously affect quality of life and make it more difficult for patients to cope with cancer and treatment side effects.

Mouth sores (mucositis). Mucositis is an inflammation of the inside of the mouth and throat, leading to painful ulcers and mouth sores. It occurs in up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy treatments. Mucositis can be caused by a chemotherapeutic drug directly, the reduced immunity brought on by chemotherapy, or radiation treatment to the head and neck area.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are common in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer and in some patients receiving radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Numbness, Tingling, Weakness, Headache, Difficulty Speaking (Nervous system disturbances). Nervous system disturbances can be caused by many different factors, including cancer, cancer treatments, medications, or other disorders. Symptoms that result from a disruption or damage to the nerves caused by cancer treatment (such as surgery, radiation treatment, or chemotherapy) can appear soon after treatment or many years later. See Managing Side Effects: Nervous System Disturbances for the most common symptoms.

Skin problems. The skin is an organ system that contains many nerves. Because of this, skin problems can be very painful. Because the skin is on the outside of the body and visible to others, many patients find skin problems especially difficult to cope with. Because the skin protects the inside of the body from infection, skin problems can often lead to other serious problems. As with other side effects, prevention or early treatment is best. In other cases, treatment and wound care can often improve pain and quality of life. Skin problems can have many different causes, including chemotherapy leaking out of the intravenous (IV) tube, which can cause pain or burning; peeling or burned skin caused by radiation therapy; pressure ulcers (bed sores) caused by constant pressure on one area of the body; and pruritus (itching) in patients with cancer, most often caused by leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, or other cancers. Patients taking erlotinib, cetuximab, or other similar medications may experience a rash or other skin problems specific to these drugs. Learn more about Skin Reactions to Targeted Therapies.

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia). Dysphagia occurs when a patient has trouble getting food or liquid to pass down the throat. Some patients may gag, cough, or choke when trying to swallow, while others experience pain or feel like food is stuck in the throat. Difficulty swallowing is a relatively common side effect of some cancer treatments. Potential side effects of cancer treatment that can cause swallowing difficulties include soreness, pain, or inflammation in the throat, esophagus, or mouth (mucositis); dry mouth from radiation therapy or chemotherapy; infections of the mouth or esophagus from radiation therapy or chemotherapy; swelling or constriction of the throat or esophagus from radiation therapy or surgery; and physical changes to the mouth, jaw, throat, or esophagus as a result of surgery.

After Treatment

Each year, tens of thousands of people are cured of lung cancer in the United States. After treatment for lung cancer ends, your doctor will outline a program of tests and visits to monitor your recovery and to check that the cancer has not returned. This plan may include regular physical examinations and/or medical tests. During this period, any new problem without an obvious cause that lasts for more than two weeks should be brought to the attention of your doctor or nurse.

People treated for lung cancer may continue to have symptoms, even after treatment ends. Common post-treatment problems include pain, fatigue, and shortness of breath. Feelings of depression and anxiety may also persist after treatment, and fear of the cancer returning is very common. Your doctor and nurse can help you develop a plan to manage these problems.

Nothing helps recovering people with lung cancer more than stopping smoking. There are many tools and approaches available. Enlist the support of your family, friends, nurses, and doctors-it is difficult to stop on your own.

People who develop lung cancer are at higher risk for developing a second lung cancer. Your doctor will recommend scans to monitor you for this possibility, so any new cancers can be detected at the earliest and most curable time.

People recovering from lung cancer are encouraged to follow established guidelines for good health, such as maintaining a healthy weight, eating a balanced diet, and having recommended cancer screening tests. Because many survivors of lung cancer have smoked cigarettes in the past, they are at very high risk for heart disease, stroke, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis. Certain cancer treatments can further increase these risks. Talk with your doctor to develop a plan that is best for your needs.

Moderate physical activity can help rebuild your strength and energy level. Recovering patients, even those using oxygen, are encouraged to walk for 15 to 30 minutes each day to improve their heart and lung functioning. Your doctor can help you create an appropriate exercise plan based upon your needs, physical abilities, and fitness level. Learn more about Healthy Living After Cancer.