Overview

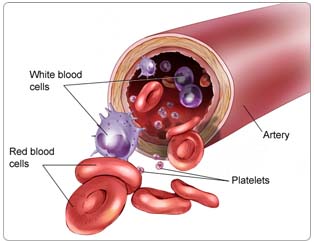

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a cancer of the blood-producing cells of the bone marrow (the spongy, red tissue in the inner part of the large bones) that primarily results in an increase in the number of white blood cells (cells that normally fight infection). CML is also sometimes called chronic granulocytic, chronic myelocytic, or chronic myelogenous leukemia. CML makes up about 9% of all new cases of leukemia.

People with CML have an acquired genetic abnormality or mutation in their bone marrow cells, in which one chromosome (a long strand of genes) breaks off and reattaches to another chromosome. This type of genetic exchange is called a translocation. In CML, part of chromosome 9 breaks off and fuses to a section of chromosome 22, and it is called the Philadelphia chromosome or Ph chromosome. The translocation causes two genes called BCR and ABL to fuse into one gene called BCR-ABL. This mutation is found only in the blood-forming cells, not in other organs of the body, and is not inherited. Hence, there is no concern about an increased risk to other family members.

The BCR-ABL gene causes myeloid cells to produce an abnormal enzyme that allows white blood cells to grow out of control. Ordinarily, the number of white blood cells is tightly controlled by the body-more white blood cells are produced during infections or times of stress, but then return to normal when the infection is cured. In CML, the abnormal BCR-ABL enzyme is like a switch that is stuck in the "on" position-it keeps stimulating the white blood cells to grow. In addition to the elevated white blood cell count, the number of blood platelets (cells that help the blood to clot) often increase, and the number of red blood cells, which carry oxygen, decrease.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing cancer. Some risk factors can be controlled, such as smoking, and some cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence the development of cancer, most do not directly cause cancer. Some people with several risk factors never develop cancer, while others with no known risk factors do. However, knowing your risk factors and communicating them to your doctor may help you make more informed lifestyle and health-care choices.

The cause of CML is not known, though researchers now understand how the disease develops from genetic changes in myeloid cells. Environmental factors account for only a small number of CML cases, and family history does not appear to play a role in the development of CML.

The following factors may raise a person's risk of developing CML:

Age. Risk of CML is higher in adults older than 60, as this cancer is most prevalent later in life. CML is uncommon in children and adolescents.

Radiation exposure. There was an increase in the rate of CML seen in Japan in long-term survivors of the atomic bombings. However, there is no proven link in the occurrence of CML following radiation therapy or chemotherapy given for other types of cancer or other diseases.

Gender. Men have a slightly higher risk of CML than women.

Symptoms

People with CML may experience the following symptoms. Sometimes, people with CML do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be caused by a medical condition that is not cancer. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your doctor.

- Fatigue (extreme tiredness) or weakness

- Excessive sweating, especially at night

- Weight loss

- Abdominal swelling or discomfort due to an enlarged spleen. This may be particularly obvious in the upper left part of the abdomen.

CML progresses slowly, and symptoms may not appear for a long time. The symptoms are usually mild at first and get worse slowly. Many people do not have any symptoms when they are diagnosed with CML.

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine more about the disease. Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis. Imaging tests may also be used. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

The following tests may be used to diagnose or monitor CML:

Blood tests. Many people are diagnosed with CML before they have any symptoms through a routine blood test, called a complete blood count (CBC), which counts the number of different kinds of cells in the blood. People with CML have high levels of white blood cells. In advanced stages of CML, there may be low levels of red blood cells (anemia) or either elevated or decreased numbers of platelets.

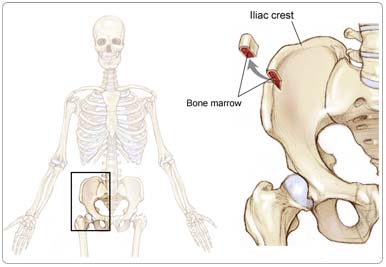

Bone marrow biopsy. In a bone marrow biopsy, a doctor takes a sample of marrow, usually from the back of the hipbone, with a needle. The cells from the marrow, along with the cells from the blood, are analyzed by a pathologist (a doctor who specializes in interpreting laboratory tests and evaluating cells, tissues, and organs to diagnose disease). Marrow samples may also undergo cytogenetic analysis.

Cytogenetics. Cytogenetics is the analysis of a cell's chromosomes, including the number, size, shape, and arrangement of the chromosomes. All people with CML have the Philadelphia chromosome or the BCR-ABL fusion gene, so the presence of either is used to confirm the diagnosis. In a small percentage of patients, there are clinical findings that suggest CML, but the patients do not have the Philadelphia chromosome or the BCR-ABL fusion gene; therefore, they have a different type of chronic myeloproliferative disease (a disease in which there is too many red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets). Treatment of this disease is different from that of CML.

Cytogenetic testing is also used to monitor treatment. The following tests are sometimes used in conjunction with cytogenetic testing:

- Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) is a test used to identify the BCR-ABL fusion gene and to monitor patients receiving treatment. This test can also be used on peripheral (circulating) blood cells or bone marrow cells to track the results of treatment.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a DNA test that can detect the BCR-ABL fusion gene and other molecular abnormalities. Patients receiving treatment may also be monitored with PCR tests. This test is quite sensitive and, depending on the one used, can detect one abnormal cell mixed among a million normal cells.

Imaging tests. Doctors may use imaging tests to determine if the cancer is affecting other parts of the body. For example, a computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan or ultrasound examination is sometimes used to assess the size of the spleen in patients with CML. A CT scan creates a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body with an x-ray machine, and an ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of the inside of the body.

Treatment

The treatment of CML depends on the phase of the disease and the patient's overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan.

Chronic phase

The immediate goals of treatment are to alleviate any symptoms the patient may be experiencing with the longer-term goal of decreasing or eliminating the cells with the Philadelphia chromosome to delay or prevent the progression of the disease to blast crisis.

Imatinib

Imatinib (Gleevec) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of all phases of CML in 2001. This drug has the unique ability to specifically inhibit the action of the BCR-ABL enzyme, which in turn results in the rapid death of the CML cells. This strategy represents a new way of treating cancer because it targets the CML cells with few harmful effects on normal cells.

This drug has changed standard treatment for CML. It is given in pill form once or twice a day and causes fewer side effects than previous treatments. Nearly all patients in the chronic stage respond to the drug with complete normalization of blood counts and shrinkage of the spleen. Most importantly, the cells with the Philadelphia chromosome are eliminated, as assessed by cytogenetic studies, in 80% to 90% of newly diagnosed patients in the chronic phase. This is called a complete cytogenetic remission (CCyR).

The relapse rate in patients whose cancer completely responds to imatinib has been very low, and it is almost certain that patients with a significant reduction in the Philadelphia chromosome will remain in chronic phase longer with imatinib, compared with previous therapies. Although it is too soon to know how long these responses will last or if patients will be cured with this medication alone, there are patients who have been successfully treated with imatinib for more than six years (since the 2001 FDA approval).

Imatinib is now considered the treatment of choice for chronic phase CML, although bone marrow transplantation may also be a primary treatment option for younger patients (see below). Side effects of imatinib are mild but can include slight nausea, changes in blood counts, fluid retention, swelling around the eyes, and muscle cramps. If a patient's CML responds well to imatinib (there is no evidence of the Philadelphia chromosome and the patient has a normal level of blood cell counts), the patient should stay on this medication indefinitely.

Measuring response to treatment

Patients receiving treatment should be monitored to see how well the treatment is working. The response of CML to imatinib includes:

- A complete hematologic response: the white blood cell and platelet counts have returned to normal, the spleen is of normal size and cannot be felt on physical examination, and the patient has no symptoms of CML

- A partial response: the blood counts are still abnormal, there may still be some immature blasts present in the blood, and the spleen may still be enlarged, although the symptoms and blood tests are improved compared with those before treatment

Other specific tests are used to detect the number of cells that have the Philadelphia chromosome or contain the BCR-ABL fusion gene. At diagnosis, the Philadelphia chromosome is present in almost all of the marrow cells. Once a patient's cancer shows a complete hematologic response, the doctor then measures the cancer's cytogenetic response.

- A complete cytogenetic response means there are no cells with the Philadelphia chromosome detected by cytogenetic analysis.

- A partial cytogenetic response means that between 1% and 34% of the cells still have the Philadelphia chromosome.

- A minor cytogenetic response means that more than 35% of the cells still have the Philadelphia chromosome.

The goal of treatment with imatinib is to achieve a complete cytogenetic response. Other more sensitive tests include FISH and PCR. Patients who have no cells with the Philadelphia chromosome by regular cytogenetic analysis are often monitored by the PCR test with the goal of a molecular response. Doctors are learning how to use these sensitive tests to help them make treatment decisions in individual patients treated with imatinib.

Dasatinib

In 2006, the FDA approved dasatinib (Sprycel) for the treatment of adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or myeloid or lymphoid blast phase CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy, including imatinib. Dasatinib is a pill that is taken twice a day.

The side effects of dasatinib include anemia, neutropenia (low levels of white blood cells), and thrombocytopenia (low platelet counts). Healthcare providers will monitor the patient's blood counts frequently after starting dasatinib and may adjust dosing or stop giving the drug temporarily if the patient's blood counts drop too low. Dasatinib may also cause bleeding, fluid retention, diarrhea, rash, headache, fatigue, and nausea.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. The drugs travel through the bloodstream to cancer cells throughout the body.

Because chemotherapy affects normal cells as well as cancer cells, many people experience side effects from treatment. Side effects depend on the specific drug and the dosage. Common side effects include nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, fatigue, low blood count, bleeding or bruising after minor cuts or injuries, numbness and tingling in the hands or feet, headaches, hair loss, and darkening of the skin and fingernails. Side effects usually go away when treatment is complete.

A drug called hydroxyurea (Hydrea) is often given initially to reduce the white blood cell count until the definite diagnosis of CML is made with the tests described above. Given orally (in pill form), the drug is effective at normalizing the blood counts and reducing the size of the spleen, but it does not eliminate the cells with the Philadelphia chromosome and does not prevent the onset of blast crisis. Although hydroxyurea has few side effects and is well tolerated, most newly diagnosed patients in chronic phase are treated with imatinib.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications. Learn more about your prescriptions through PLWC's Drug Information Resources, which provides links to searchable drug databases.

Stem cell transplantation/bone marrow transplantation

The only proven curative treatment for CML is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) using cells from a donor whose tissue type matches that of the patient (called an allogeneic transplant). Hematopoietic stem cells are special cells that can develop into different kinds of blood cells, such as red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets. Stem cells are found both in the circulating blood and in the bone marrow.

In an allogeneic SCT, the patient is treated with high doses of chemotherapy and (sometimes) with total body radiation therapy to kill as many cancer cells as possible and to prevent the patient's immune system from rejecting the donated stem cells. After the high-dose therapy is given, stem cells obtained from a healthy donor (usually a sibling) are infused into the patient's bloodstream. Within two to three weeks, these cells will mature into healthy, blood-producing tissue. The patient may need antibiotics to prevent and treat infection and transfusions of red blood cells and platelets.

The short-term side effects of the high-dose chemotherapy (and radiation therapy, if given) regimen may include nausea, vomiting, hair loss, diarrhea, and mouth sores. Long-term side effects may include fertility problems, cataracts, or heart problems.

The major risk of allogeneic transplantation is that the donated cells may recognize the normal host tissues as "foreign" and attack that tissue, known as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). GVHD is a serious complication of allogeneic transplantations and can be fatal. A variety of different drugs that suppress the immune system are given to both prevent and treat GVHD should it occur. Some amount of GVHD is helpful, however, in keeping the leukemia from returning.

Although transplantation can successfully cure CML, unsuccessful allogeneic transplantations can actually shorten a patient's life compared with less intensive treatments. GVHD is a greater problem in older patients and in those with other medical complications. Therefore, transplantation is usually considered for younger patients in the early stages of chronic phase and in good overall health.

Imatinib has been so effective in suppressing CML cells that SCT is now generally recommended for patients whose cancer does not respond to imatinib or recurs or worsens while being treated with imatinib. Because the decision to undergo transplantation versus treatment with imatinib or dasatinib can be complex and difficult, patients are strongly encouraged to seek the advice of doctors experienced in the treatment of CML.

Learn more by reading the PLWC Feature series, Understanding Bone Marrow and Stem Cell Transplantation.

Interferon

Interferon is a type of biologic therapy, which is the use of substances made by the body or created in a laboratory to support or stimulate the body's immune system to fight cancer. Interferon can reduce the white blood cell count and sometimes decrease the number of cells that have the Philadelphia chromosome. It is given by daily injections under the skin and causes flu-like side effects, such as fever, chills, and loss of appetite.

When given on a chronic basis, it can cause fatigue, loss of energy, and memory changes. Interferon therapy was the primary treatment for chronic phase CML before imatinib became available. A clinical trial showed that imatinib was more effective than interferon, producing much higher response rates with fewer side effects. Therefore, interferon is no longer recommended as initial treatment for CML, although it is being evaluated in combination with imatinib in some clinical trials.

Accelerated phase

The same drugs used in chronic phase CML may also be used in the accelerated phase. Although treatment with imatinib can be successful during this stage, the response rate is much lower than in chronic phase, and most patients have a relapse within about two years. Therefore, SCT should be considered when possible. If SCT is inadvisable or if a compatible donor cannot be identified, the treatment plan may include dasatinib or experimental treatments being tested in clinical trials.

Blastic phase

Treatment with imatinib produces short responses that last a few months in a minority of patients in blast crisis, but it can help to control the CML while transplantation is being arranged. Transplantation is less successful than in chronic phase, but some patients have been successfully treated with this approach. Many people with CML in blastic phase are treated with chemotherapy usually used for patients with acute myeloid leukemia. The chance of remission from this approach is about 20%; most patients' leukemia recurs (comes back) within weeks to a few months. Hydroxyurea is frequently given to patients because it can help control blood counts. If transplantation is not an option, the doctor may recommend experimental treatments being tested in clinical trials.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to CML and its treatments, especially bone marrow transplants. Imatinib and dasatinib do not generally cause these side effects. For more detailed information on managing these and other side effects of cancer and cancer treatment, visit the PLWC Managing Side Effects section.

Constipation. Constipation is the infrequent or difficult passage of stool. About 40% of patients in palliative care (care given to improve a patient's quality of life) experience constipation, and about 90% of patients taking opioid medications (such as morphine) experience constipation. Constipation includes fewer bowel movements, stools that are abnormally hard, discomfort, or a feeling of incomplete rectal emptying. Patients with constipation can experience pain, swelling in the abdomen, loss of appetite, nausea and/or vomiting, inability to urinate, and confusion.

Fatigue. Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness and is the most common problem that patients with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously affect family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even affect the will to live.

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin-sometimes unnoticeably-and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, the hair loss is usually temporary, and the hair often grows back.

Infection. An infection occurs when harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi (such as yeast) invade the body and the immune system is not able to destroy them quickly enough. Patients with cancer are more likely to develop infections because both cancer and cancer treatments (particularly chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the bones or extensive areas of the body) can weaken the immune system. Symptoms of infection include fever (temperature of 100.5°F or higher); chills or sweating; sore throat or sores in the mouth; abdominal pain; pain or burning when urinating or frequent urination; diarrhea or sores around the anus; cough or breathlessness; redness, swelling, or pain, particularly around a cut or wound; and unusual vaginal discharge or itching.

Mouth sores (mucositis). Mucositis is an inflammation of the inside of the mouth and throat, leading to painful ulcers and mouth sores. It occurs in up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy. Mucositis can be caused by chemotherapy directly, the reduced immunity brought on by chemotherapy, or radiation therapy to the head and neck area.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are preventable, treatable, and may occur in patients receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Neutropenia. Neutropenia is an abnormally low level of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell that helps the body fight infection. Neutrophils fight infection by destroying bacteria. Patients who have neutropenia are at increased risk for developing serious bacterial infections because there are not enough neutrophils to destroy harmful bacteria. Neutropenia occurs in about 50% of patients receiving chemotherapy and is common in patients with leukemia.

Skin problems. The skin is an organ system that contains many nerves, so skin problems can be painful. Many patients find skin problems especially difficult to cope with because the skin visible to others. Because the skin protects the inside of the body from infection, skin problems can often lead to other serious problems. In other cases, treatment and wound care can often improve pain and quality of life. Skin problems can have many different causes, including chemotherapy leaking out of the intravenous (IV) tube, which can cause pain or burning; peeling or burned skin caused by radiation therapy; pressure ulcers (bed sores) caused by constant pressure on one area of the body; and pruritus (itching) in patients with cancer, most often caused by leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, or other cancers. As with other side effects, prevention or early treatment is best.

Thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia is an unusually low level of platelets in the blood. Platelets, also called thrombocytes, are the blood cells that stop bleeding by plugging damaged blood vessels and helping the blood to clot. Patients with low levels of platelets bleed more easily and are prone to bruising. Platelets and red and white blood cells are made in the bone marrow, a spongy, fatty tissue found on the inside of larger bones. Certain types of chemotherapy can damage the bone marrow so that it does not make enough platelets. Thrombocytopenia caused by chemotherapy is usually temporary. Other medications used to treat cancer may also lower the number of platelets. In addition, a patient's body can make antibodies to the platelets, which lowers the number of platelets.

After Treatment

As treatment for CML ends (such as a transplant) or continues long-term (such as treatment with imatinib), talk with your doctor about developing a follow-up care plan. This plan may include regular physical examinations and/or medical tests to monitor your recovery for the coming months and years.

People treated for CML and in remission should receive regular follow-up examinations for several years to detect early evidence of relapse or late effects (side effects that occur years after treatment) of treatment. People treated for CML are encouraged to follow established recommendations for good health, such as quitting smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, and receiving appropriate screening for other types of cancer.

For some patients, imatinib is an ongoing cancer therapy. Any decision to discontinue this treatment would be decided by a patient and doctor, based these how well imatinib continues to work and the extent of the side effects.