Overview

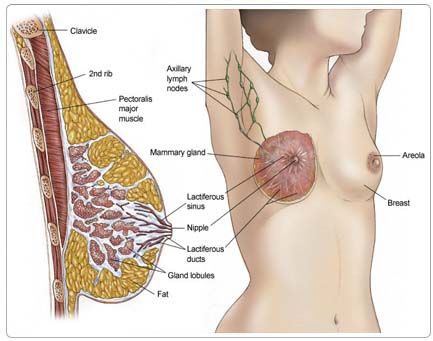

The breast is composed of mainly fatty tissue. Within this tissue is a network of lobes, which are made up of tiny, tube-like structures called lobules that contain milk glands. Tiny ducts connect the glands, lobules, and lobes and carry the milk from the lobes to the nipple, located in the middle of the areola (darker area that surrounds the nipple of the breast). Blood and lymph vessels run throughout the breast; blood nourishes the cells, and the lymph system drains bodily waste products. The lymph vessels connect to lymph nodes.

About 90% of all breast cancers originate in the ducts or lobes. Almost 75% of all breast cancers begin in the cells lining the milk ducts and are called ductal carcinomas. Cancer that begins in the lobules is called lobular carcinoma. Lobular carcinoma has a higher chance of occurring in the contralateral (the other) breast, either at the time of diagnosis or in the future.

If the disease has spread outside of the duct and into the surrounding tissue, it is called invasive or infiltrating ductal carcinoma. If the disease has spread outside of the lobule, it is called invasive or infiltrating lobular carcinoma. Disease that has not spread is called in situ, meaning "in place." The course of in situ disease, as well as its treatment, depends on whether it is ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing a disease, including cancer. There are risk factors that can be controlled, such as smoking, and risk factors that cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence disease, they do not necessarily cause cancer. Some people with several risk factors never develop the disease, while others with no known risk factors do. Knowing your risk factors and communicating with your doctor can help guide you in making wise lifestyle and health-care choices.

Many cases of breast cancer occur in women with no obvious risk factors. This means that women need to be aware of possible changes in their breasts, perform self-examinations, and schedule clinical breast examinations and mammograms. It is likely that multiple risk factors influence the development of breast cancer. The following factors can raise a person's risk of developing breast cancer:

Age. The risk of developing breast cancer increases as a woman ages, with the majority of breast cancers developing in women over 50.

Race. Although white women are more likely to develop breast cancer, black women are more likely to die from the disease. The reasons for this are unclear and probably involve both socioeconomic and biologic factors.

Previous history of breast cancer. Women who have had breast cancer in one breast have three to four times the risk of breast cancer in their opposite breast.

A family history of breast cancer. Women who have a first-degree relative (mother, sister, daughter) diagnosed with breast cancer are at increased risk for the disease. More than one first-degree relative with breast cancer elevates that risk, particularly if the cancer occurred before menopause.

A history of ovarian cancer. Because ovarian cancer is also associated with exposure to hormones, a history of ovarian cancer can increase the risk of breast cancer. Some breast cancer gene mutations, such as breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) and breast cancer gene 2 (BRCA2) may increase the risk of both ovarian and breast cancers (see explanation below).

A genetic predisposition. Mutations to the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes are associated with increased breast cancer risk. Blood tests are available to test for known mutations to these genes, but are not recommended for everyone and only after a person has received appropriate genetic counseling. Researchers estimate that breast cancers caused by these genes make up only 2% to 3% of all breast cancers. Learn more about The Genetics of Breast Cancer.

Estrogen exposure. Estrogen is a hormone in women that controls the development of secondary sex characteristics (such as breast development). A woman's production of estrogen decreases at menopause. Doctors think that exposure to estrogen for a long time may increase breast cancer risk.

- Women who began menstruating before age 12 or went through menopause after age 55 have a higher risk of breast cancer because their breast cells have been exposed to estrogen for longer periods.

- Women who have their first pregnancy after age 30 or who have never had a full-term pregnancy have a higher risk of breast cancer. Pregnancy may protect against breast cancer, because it pushes breast cells into their final phase of maturation.

- Oral contraceptive (birth control pills) use may slightly increase a woman's risk of breast cancer, but the risk disappears after 10 years in women who have stopped taking oral contraceptives.

- Recent use (within the past five years) of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and long-term use (several years or more) of HRT increases a woman's risk of breast cancer.

Atypical hyperplasia of the breast. This condition is characterized by abnormal, but not cancerous, cells found in a breast biopsy. Atypical hyperplasia is a risk factor for breast cancer.

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). This condition describes abnormal cells found in the lobules or glands of the breast. LCIS increases the risk of developing invasive breast cancer (cancer that spreads into surrounding tissues). In some patients with LCIS, a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy (preventive removal of both breasts) is recommended to reduce the risk of future breast cancer.

Lifestyle factors. As with other types of cancer, studies continue to show that various habits may contribute to the development of breast cancer.

- Obesity. Recent studies have shown that being obese or even overweight increases a woman's risk of breast cancer.

- Lack of exercise. Exercise lowers hormone levels and boosts the immune system; lack of exercise contributes to obesity.

- Alcohol use. Drinking more than one alcoholic drink per day may raise the risk of breast cancer.

Radiation. High doses of radiation may increase a woman's risk of breast cancer. An increased risk of breast cancer has been observed in long-term survivors of atomic bombs, people with lymphoma treated with radiation therapy to the chest, people undergoing large numbers of x-rays for tuberculosis or nonmalignant conditions of the spine, and children treated with radiation for ringworm.

Prevention

Currently, there are no proven means to prevent breast cancer. A woman's best chance of surviving breast cancer is early detection through regular self-breast examinations, clinical breast examinations, and mammography (an x-ray of the breast that can detect tumors too small to be felt). If cancer is found at an early stage, treatment is more likely to be successful.

For women with especially strong family histories of breast cancer, a prophylactic mastectomy may be considered. This appears to reduce the risk of developing breast cancer by at least 95%.

Women who are at higher than normal risk for developing breast cancer may consider chemoprevention (the use of drugs to reduce breast cancer risk). Results of large clinical trials (research studies that test new treatments) have shown that selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as tamoxifen (Nolvadex), can reduce a woman's risk of developing breast cancer. A SERM is a medication that blocks estrogen receptors in some tissues and not others.

In addition, tamoxifen can reduce the risk of the cancer recurring once a woman has been treated for breast cancer. Like estrogen, these drugs help increase bone density in postmenopausal women and protect the cardiovascular system. However, unlike estrogen, SERMs do not promote the development of breast cells into cancer cells.

Symptoms

Women with breast cancer may experience the following symptoms. Sometimes, women with breast cancer do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be similar to symptoms of other medical conditions. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your doctor.

However, many breast cancers develop with no symptoms at all. Some tumors may be visible on a mammogram before symptoms develop. It is important for all women to be familiar with the appearance, feel, shape, and texture of their breasts in order to detect changes as soon as they occur.

- New lumps (many women normally have lumpy breasts) or a thickening in the breast or under the arm

- Nipple tenderness, discharge, or physical changes (such as a nipple turned inward or a persistent sore)

- Skin irritation or changes, such as puckers, dimples, scaliness, or new creases

- Warm, red, swollen breasts with a rash resembling the skin of an orange (peau d'orange)

- Pain in the breast (usually not a symptom of breast cancer, but should be reported to a doctor)

Diagnosis

Doctors use many tests to diagnose cancer and determine if it has metastasized. Some tests may also determine which treatments may be the most effective. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis. Imaging tests may be used to find out whether the cancer has metastasized. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- Age and medical condition

- The type of cancer

- Severity of symptoms

- Previous test results

The diagnosis of breast cancer usually begins when a woman or doctor discovers a mass or abnormal calcification (tiny spot of calcium usually found on an x-ray) on a screening mammogram, or an abnormality in the woman's breast by clinical examination or self-examination. Several tests may be done to confirm a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Treatment

The treatment of breast cancer depends on the size and location of the tumor, whether the cancer has spread, and the person's overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan.

Even though the doctor will tailor the treatment for breast cancer specifically for each patient, there are some general steps for treating breast cancer. Primarily, the goal of the initial therapy for early-stage disease is to remove any visible tumor. Therefore, doctors will recommend surgery to remove the tumor. Most of the time radiation therapy to the remaining breast tissue will be recommended, although there are certain situations where it is not recommended (for example, in patients older than age 70).

The next step in the management of early-stage disease is to reduce the risk of the disease recurring and eliminate any remaining cancer cells. If a tumor is large or lymph nodes are involved, the doctor may recommend additional therapy, such as radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and/or hormonal therapy. Recurrent cancer is treated in a variety of ways.

When planning the treatment for breast cancer, the doctor will consider many factors, including:

- The stage and grade of the tumor

- The tumor's hormone receptor status (ER, PR) (see Diagnosis)

- The patient's age and general health

- The patient's menopausal status

- The presence of known mutations to breast cancer genes

- Factors that may signify an aggressive tumor, such as HER-2/neu amplifications (see Diagnosis)

Surgery

Generally, the smaller the tumor, the more surgical options a patient has. The types of surgery include the following:

- A lumpectomy removes the tumor and a small clean (disease-free) margin of tissue around the tumor. For an invasive cancer, follow-up radiation therapy is routinely given to the disease site.

- A partial mastectomy removes the tumor, an area of normal tissue, and part of the lining over the chest muscle where the tumor was located. This surgery is similar to a lumpectomy. It is also called a segmental mastectomy and requires follow-up radiation therapy.

- A total mastectomy removes the entire breast, but not the underarm lymph nodes. This surgery is also called a simple mastectomy.

- A modified radical mastectomy removes the breast, some of the underarm lymph nodes, and one of the smaller chest muscles.

- Axillary lymph node dissection involves the surgeon removing lymph nodes from under the arm and having them examined by a pathologist for cancer cells. Because each person has different number of underarm lymph nodes, the actual number of lymph nodes removed varies from four to 60.

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy is a procedure in which the surgeon finds and removes the sentinel (first) lymph node (generally one to three nodes) that receives drainage from the breast. The pathologist then examines it for cancer cells. To identify the sentinel lymph node, the surgeon injects a dye and/or a radioactive tracer into the area around the person's primary breast tumor. The dye or tracer will travel to the lymph nodes, arriving at the sentinel node first. The surgeon can find the node when it turns color (if the dye is used) or emits radiation (if the tracer is used). Sentinel lymph node biopsy has a lower risk of lymphedema (swelling of the arm) than axillary lymph node dissection, which removes most of the lymph nodes from under the arm. If the sentinel node is cancer-free, research has shown that there is a good possibility that the subsequent nodes will also be free of cancer and no further surgery of the lymph nodes is performed. If the sentinel lymph node shows cancer is present, then the surgeon will perform an axillary lymph node dissection. For more information, read the ASCO Patient Guide: Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Early Stage Breast Cancer

Most patients with invasive cancer will undergo either sentinel lymph node biopsy or an axillary lymph node dissection. For those with positive sentinel nodes, an axillary lymph node dissection is still considered necessary. Research is underway to assess if this is continues to be true.

To summarize, surgical treatment options include the following:

- Lumpectomy and radiation therapy

- Partial mastectomy and radiation therapy

- Total mastectomy

- Modified radical mastectomy

For invasive breast cancer, the combination of lumpectomy or partial mastectomy, underarm lymph node removal, and radiation therapy has been proven in clinical trials to be as effective as a modified radical mastectomy.

Women are encouraged to talk with their doctors about which surgical option is right for them. More aggressive surgery (such as a mastectomy) is not always better and may result in additional complications.

Women who undergo a mastectomy may wish to consider breast reconstruction, which is surgery to rebuild the breast. Reconstruction may be done with tissue from another part of the body, or with synthetic implants. A woman may choose to have this done at the time of mastectomy or at some point in the future.

Adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant therapy is treatment that is given in addition to surgery to decrease the risk of the breast cancer returning. Adjuvant therapies include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapies, and targeted therapies. They are intended to eliminate any potential breast cancer cells lingering in the body. Adjuvant therapy decreases the risk of recurrence, but does not necessarily eliminate it.

Along with staging, other sophisticated tools can help determine prognosis and help you and your doctor make decisions about adjuvant therapy. The website Adjuvant! (www.adjuvantonline.com) is one such tool that your doctor can access to interpret a variety of prognostic factors. This website should only be used with the interpretation of your doctor.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy is given regularly for a number of weeks following a lumpectomy or partial mastectomy to eliminate remaining cancer cells near the tumor site or elsewhere within the breast. Radiation therapy is also recommended for some women after a mastectomy depending upon the size of their tumor, number of cancerous lymph nodes under the arm, and width of the margin of resection obtained by the surgeon. Radiation therapy may be given before surgery to shrink a large tumor and make it easier to remove, although this approach is rare.

Radiation therapy is effective in reducing the chance of breast cancer returning in both the breast and the chest wall. The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation therapy given from a machine outside the body. When radiation treatment is given using implants, it is called internal radiation therapy or bracyhterapy.

Radiation therapy can cause side effects, including fatigue, swelling, and skin changes. A small amount of the lung can be affected by the radiation, although the risk of pneumonitis, or a radiation-related pneumonia, is rare.

In the past, with older equipment and techniques of radiation therapy, women treated for left-sided breast cancers had a small increase in the long-term risk of heart disease. Modern techniques are now able to spare most of the heart from radiation damage. While exposure to radiation is thought to be a risk factor of cancer after many years, less than one in 500 survivors will develop a different kind of cancer, other than a breast cancer, within the area that was treated. Clinical studies comparing lumpectomy and radiation therapy with mastectomy have not shown a difference in the number of patients developing or dying of other cancers within a 20-year time span.

For more information, read the PLWC Feature: Understanding Radiation Therapy, the PLWC Feature: Radiation Therapy—Your Personal Experience, and the PLWC Feature: Side Effects of Radiation Therapy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. It travels through the bloodstream to cancer cells throughout the body and destroys cancer cells that have migrated from the original site of the tumor. Chemotherapy may be given orally (by mouth)or intravenously (injected into a vein) and is usually given in cycles. Chemotherapy generally does not require a hospital stay; it is given in an outpatient setting. Chemotherapy may be neoadjuvant therapy (given before surgery to shrink a large tumor) or adjuvant therapy (given after surgery to reduce the risk that the cancer returns). Chemotherapy may also be given at the time of a breast cancer recurrence. Patients in clinical trials may be offered new drugs or new combinations of existing drugs.

Different drugs are useful for different cancers, and research has shown that combinations of certain drugs are more effective than individual ones. The following drugs may be used to treat breast cancer:

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar)

- Methotrexate (Amethopterin)

- Fluorouracil (5-FU, Efudex)

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin, Rubex)

- Epirubicin (Ellence)

- Paclitaxel (Taxol)

- Docetaxel (Taxotere)

- Vinorelbine (Navelbine)

- Capecitabine (Xeloda)

- Protein bound paclitaxel (Abraxane)

Common combinations of drugs include the following:

- CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-FU)

- CAF (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-FU)

- CEF (cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and 5-FU)

- EC (epirubicin and cyclophosphamide)

- AC (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide)

- TAC (docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide)

- AC followed by T (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel)

- TC (docetaxel and cyclophosphamide)

These drugs are powerful and affect both healthy and cancerous cells in the body. Normal cells that grow quickly, such as those lining the gastrointestinal tract or hair follicles, may be damaged or killed along with cancer cells. Side effects can include fatigue, nausea and vomiting, lowered white blood cell count and a corresponding increased risk of infection, mouth sores, hair loss, and premature menopause. Most of these side effects go away once treatment is stopped and are not long term. However, long-term effects may occur including heart damage, nerve damage, or secondary cancers.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions. Learn more about your prescriptions through PLWC's Drug Information Resources, which provides links to multiple drug databases.

Hormonal therapy

Hormonal therapy is useful to manage a tumor that tests positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors. This type of tumor uses hormones to fuel its growth. Blocking the hormones usually limits the growth of the tumor.

If it is determined that the tumor is hormone receptor-positive (uses estrogen or progesterone to grow [see Diagnosis]), than hormonal treatment may be used alone or together with chemotherapy. Examples of hormonal therapy used as adjuvant therapies are tamoxifen, anastrozole (Arimidex), letrozole (Femara), and exemestane (Aromasin).

Tamoxifen is the drug that researchers have studied the longest for use as a hormonal therapy. It blocks estrogen from binding to tumor cells. It has been shown to be effective for reducing the risk of recurrence in the treated breast, the risk of developing cancer in the other breast, and the risk of developing cancer in women with no history of the disease but who are at higher than average risk for developing breast cancer. Current research shows that there is no benefit for taking tamoxifen longer than five years for node-negative breast cancer.

The side effects of tamoxifen include hot flashes, a small increased risk of uterine cancer and uterine sarcoma, and an increase in the risk of blood clots. Tamoxifen can be effective in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

In postmenopausal women who have an increased risk of developing breast cancer, raloxifene has shown to be another hormonal therapy that is as effective as tamoxifen in preventing invasive breast cancer, but not as effective in preventing noninvasive cancers, such as DCIS. The side effects of raloxifene include a small risk of blood clots, leg and joint pain, hot flashes, pain during sexual intercourse, and vaginal dryness. Raloxifene has not been evaluated in premenopausal women, and it is not considered a substitute for tamoxifen for adjuvant therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Raloxifene is not recommended for treatment of invasive breast cancer.

Aromatase inhibitors decrease the production of estrogen and are effective in postmenopausal women. They work by blocking the aromatase enzyme, which is necessary for the production of estrogen. They are emerging as the preferred treatment for women with hormone-sensitive cancers. Several of these drugs include anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane. For more information, please read the ASCO Technology Assessment for Patients: Aromatase Inhibitors for Early Breast Cancer.

Targeted therapy

Several promising new breast cancer drugs work by stopping the action of abnormal proteins that cause cells to grow and divide out of control. Monoclonal antibodies target proteins that are present in unusually large amounts in breast cancer cells.

- Trastuzumab is approved for both the treatment of advanced breast cancer and as an adjuvant therapy for early stage breast cancer for tumors that overexpress HER-2/neu. Data presented at the 2005 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting demonstrated an approximate 50% decrease in relapse and an improvement in survival in women with early breast cancer with a HER-2/neu-positive breast cancer who received trastuzumab either with or after adjuvant chemotherapy. At this time, one year of trastuzumab is recommended. Patients receiving trastuzumab have a 3% to 4 % risk of heart problems, and this risk is increased if a patient has additional risk factors for heart disease. These heart problems do not always go away, but they are usually treatable with medication. Ongoing research is assessing how much trastuzumab is enough (from nine weeks up to two years).

- Bevacizumab (Avastin) is an antiangiogenic monoclonal antibody under evaluation in clinical trials. Anti-angiogenesis agents block angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels), which is necessary for tumor growth and metastasis. When combined with paclitaxel, bevacizumab appears to increase the response rate and length of response compared with paclitaxel alone in women whose breast cancer has spread.

- For women with HER-2/neu-positive breast cancer that no longer responds to trastuzumab, a new drug called lapatinib (Tykerb) may slow the growth of breast cancer when combined with capecitabine. The combination of lapatinib and capecitabine is approved for the treatment of women with advanced or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer who have previously been treated with chemotherapy and trastuzumab.

Recurrent breast cancer

Breast cancer is called recurrent if the cancer has come back after it was first diagnosed and treated. It may come back in the breast (a local recurrence); in the chest wall; or in another part of the body, including distant organs (such as the lungs, liver, and bones) called distant metastases.

Breast cancer may also spread to other organs such as the brain, the opposite breast, adrenal glands, spleen, and ovaries. If the tumor is metastatic (spread outside of the breast or local lymph nodes), it is generally not curable. The goal of treatment for advanced disease is to achieve remission (temporary or permanent absence of disease) or slow the growth of the tumor. Some patients live years after a recurrence of breast cancer and may undergo many different treatments. With the advent of earlier detection methods and new therapies, breast cancer may be considered a chronic disease for some patients.

Generally, a recurrence is detected when a person has symptoms. Even though there are tests that may detect a metastatic recurrence before the onset of symptoms, research has shown that tests do not improve the response to treatments used for advanced disease, nor do they prolong life.

Once metastatic disease is detected, a woman may undergo surgery to remove the metastasis or receive chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapy (such as trastuzumab) to control it. Signs and symptoms depend on the site of the recurrence and may include:

- A lump under the arm or along the chest wall

- Bone pain or fractures, which may signal bone metastases

- Headaches or seizures, which may signal brain metastases

- Chronic coughing or trouble breathing, which may signal lung metastases

Other symptoms may be related to the location of metastasis and may include changes in vision, changes in energy levels, feeling ill, or extreme fatigue.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to breast cancer and its treatments. For more detailed information on managing these and other side effects of cancer and cancer treatment, visit the PLWC Managing Side Effects section.

Anemia. Anemia is common in people with cancer, especially those receiving chemotherapy. Anemia is an abnormally low level of red blood cells (RBCs). RBCs contain hemoglobin (an iron protein) that carries oxygen to all parts of the body. If the level of RBCs is too low, parts of the body do not get enough oxygen and cannot work properly. Most people with anemia feel tired or weak. The fatigue (tiredness) associated with anemia can seriously affect quality of life and make it more difficult for patients to cope with cancer and treatment side effects.

Fatigue. Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness, and is the most common problem that people with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously affect family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even affect the will to live.

Fluid in the abdomen (ascites). Ascites is the buildup of fluid in the abdomen, in the area around the organs known as the peritoneal cavity. Ten percent of all ascites is caused by cancer and is called malignant ascites. Most cancer-related ascites appears in patients with cancers of the ovary, endometrium (lining of the uterus), breast, colon, gastrointestinal (GI) system, or pancreas. These cancers can cause fluid to build up in the body. People with ascites may experience weight gain, abdominal swelling, a sense of fullness or bloating, a sense of heaviness, indigestion, nausea and/or vomiting, changes to the navel, hemorrhoids (a condition that causes painful swelling near the anus), or ankle swelling.

Fluid in the arms or legs (lymphedema). Lymphedema is the abnormal buildup of fluid in the lymphatic system, the series of channels and nodes (small sacs that hold fluid) that carries lymph through the body and helps fight infection and disease. Lymph is a clear liquid that carries protein and cells that fight infection. When cancer metastasizes, cells first go to the lymph nodes and then are carried to other parts of the body. Lymphedema can develop immediately after cancer surgery or radiation therapy, or it can develop months or years later. About 15% of women who have modified radical mastectomies develop lymphedema. The most common causes of lymphedema include surgery to remove the lymph nodes, especially for breast cancer, prostate cancer, or melanoma; radiation therapy to the lymph nodes; metastatic cancer; bacterial or fungal infection; injury to the lymph nodes; and other diseases involving the lymph system.

Fluid around the lungs (malignant pleural effusion). A pleural effusion is a condition characterized by extra fluid building up in the pleural space, the space between the edge of the lungs and the chest wall. A malignant pleural effusion is caused by cancer that grows in the pleural space. About half of patients with cancer develop a pleural effusion. More than 75% of patients with a malignant pleural effusion have lymphoma or cancers of the breast, lung, or ovary. The symptoms of a pleural effusion include dyspnea (shortness of breath), dry cough, pain, feeling of chest heaviness, inability to exercise, and malaise (feeling unwell).

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin-sometimes unnoticeably-and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, the hair loss is usually temporary, and the hair often grows back.

Hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia is an unusually high level of calcium in the blood. Hypercalcemia can be life threatening and is the most common metabolic disorder associated with cancer, occurring in 10% to 20% of patients with cancer. While most of the calcium in the body is stored in the bones, about 1% of the body's calcium circulates in the bloodstream. Calcium is important for many bodily functions, including bone formation, muscle contractions, and nerve and brain function. Patients with hypercalcemia may experience loss of appetite, nausea and/or vomiting; constipation and abdominal pain; increased thirst and frequent urination; fatigue, weakness, and muscle pain; changes in mental status, including confusion, disorientation, and difficulty thinking; and headaches. Severe hypercalcemia can be associated with kidney stones, irregular heartbeat or heart attack, and eventually loss of consciousness and coma.

Infection. An infection occurs when harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi (such as yeast) invade the body and the immune system is not able to destroy them quickly enough. Patients with cancer are more likely to develop infections because both cancer and cancer treatments (particularly chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the bones or extensive areas of the body) can weaken the immune system. Symptoms of infection include fever (temperature of 100.5°F or higher); chills or sweating; sore throat or sores in the mouth; abdominal pain; pain or burning when urinating or frequent urination; diarrhea or sores around the anus; cough or breathlessness; redness, swelling, or pain, particularly around a cut or wound; and unusual vaginal discharge or itching.

Menopausal symptoms in women. Up to 40% of women experience menopausal symptoms because of breast cancer or its treatments. Menopausal symptoms may depend on the type of therapy and may include hot flashes; night sweats; vaginal dryness, itching, irritation, or discharge; painful sexual intercourse; difficulties with bladder control; depressed feelings; and insomnia. Premenopausal women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer may undergo menopause at an earlier age than expected.

Mouth sores (mucositis). Mucositis is an inflammation of the inside of the mouth and throat, leading to painful ulcers and mouth sores. It occurs in up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy. Mucositis can be caused by chemotherapy directly, the reduced immunity brought on by chemotherapy, or radiation treatment to the head and neck area.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are common in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer and in some patients receiving radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Sexual dysfunction. Sexual dysfunction is common in all people, affecting up to 43% of women and 31% of men. It may be even more common in patients with cancer, because of treatments, the tumor, or stress. Many people, with or without cancer, find it intimidating to discuss sexual problems with their doctors. Sexual problems are most commonly caused by body changes from cancer surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy, hormone changes, fatigue, pain, nausea and/or vomiting, medications that reduce libido (desire for sex), fear of recurrence, stress, depression, and anxiety. Symptoms of sexual dysfunction generally fall into four categories: desire disorders, arousal disorders, orgasmic disorders, and pain disorders.

Skin problems. The skin is an organ system that contains many nerves. Because of this, skin problems can be very painful. Because the skin is on the outside of the body and visible to others, many patients find skin problems especially difficult to cope with. Because the skin protects the inside of the body from infection, skin problems can often lead to other serious problems. As with other side effects, prevention or early treatment is best. In other cases, treatment and wound care can often improve pain and quality of life. Skin problems can have many different causes, including chemotherapy leaking out of the intravenous (IV) tube, which can cause pain or burning; peeling or burned skin caused by radiation therapy; pressure ulcers (bed sores) caused by constant pressure on one area of the body; and pruritus (itching) in patients with cancer, most often caused by leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, or other cancers.

Weight gain. Although it is more common to lose weight during cancer treatment, some patients with cancer gain weight. Slight increases in weight during cancer treatment are generally not problematic. However, significant weight gain may affect a patient's health and the ability to tolerate treatments. Chemotherapy, steroid medications, and hormone therapies can cause weight gain.

After Treatment

After treatment for breast cancer ends, talk with your doctor about developing a follow-up care plan. This plan may include regular physical examinations and/or medical tests to monitor your recovery. The recommendations for breast cancer follow-up care usually include regular physical examinations and mammograms.Specific information can be found in the ASCO Patient Guide: Follow-up Care for Breast Cancer.

Breast cancer can recur in the breast or other areas of the body. The symptoms of a cancer recurrence include a new lump in the breast, under the arm, or along the chest wall; bone pain or fractures; headaches or seizures; chronic coughing or trouble breathing; extreme fatigue; and/or feeling ill. Talk with your doctor if you experience these or other symptoms. For some people, the possibility of recurrence becomes overwhelming.

Some patients experience breathlessness, a dry cough, and/or chest pain two to three months after finishing radiation therapy because the treatment can cause swelling and fibrosis (hardening or thickening) of the lungs. These symptoms are usually temporary. Talk with your doctor if you develop any new symptoms after radiation therapy or if the side effects are not going away.

Women taking tamoxifen should have yearly pelvic exams, because this drug can increase the risk of uterine cancer. Tell your doctor or nurse if you notice any abnormal vaginal bleeding or other new symptoms.

Women who are taking an aromatase inhibitor, such as anastrozole, exemestane, or letrozole, may consider having a bone density test, as these drugs may cause some bone loss.

Women recovering from breast cancer are encouraged to follow established guidelines for good health, such as maintaining a healthy weight and diet and having recommended cancer screening tests. Talk with your doctor to develop a plan that is best for your needs. Moderate physical activity can help you rebuild your strength and energy level. Your doctor can help you create a safe exercise plan based upon your needs, physical abilities, and fitness level.